When I started writing my novel Turin, I believed I understood what the book was about. It began with my grandfather, a Jew from Turin who was forced to leave everything behind after Mussolini’s racial laws. For a long time, I tried to connect his story with the Italian gialli films I had been obsessed with in my twenties. Those films depicted an Italy caught between tradition and modernity, a country uneasy with new sexual and social freedoms, still shadowed by fascism and by the collapse of older moral structures. The pairing was strange, but what stayed with me was their atmosphere: violence turned into spectacle, decadence masquerading as depth, a world trying to convince itself that nothing fundamental had been lost.

Over time, Nietzsche entered the book almost without my noticing. I had always read him, and he has been one of the writers who changed how I perceive reality. In a strange way he seemed to hold these precarities together. Like my grandfather, he was haunted by the past and unsettled by a culture that was beginning to prefer spectacle to substance. At the same time, he was someone who loved Italian life, its intensity, its emotional excess, its song. He was also, like my grandfather, a devotee of Wagner’s music, at least at first, and later came to see Wagner as a dangerous inculcator of myth rather than a restorer of a ‘noble’ past. My grandfather’s discomfort with that world needs no explanation.

And of course, there is the simple fact that Nietzsche’s most fevered period of writing, and his collapse, took place in Turin in 1888 and 1889.

I had always felt a kind of fear toward my grandfather, a mixture of awe, guilt and distance. I was often told I resembled him in both temperament and appearance. Over time, the idea of the father – real or metaphorical – who must die for the son to exist began to creep into the work. Not in a psychoanalytic sense, but existentially. Nietzsche had to abandon Schopenhauer, then Wagner. His biological father died when he was a child. That sense of loss and search for orientation kept returning to me as I wrote.

The gialli idea faded away, but their underlying world remained: a world where violence had lost weight, where a unifying myth had dissolved. Or, in Nietzsche’s language, the world after the death of God.

So, Turin emerged slowly, and often painfully. It was meant to be a book about collapse. Nietzsche at the edge of madness in a city that held him together while also undoing him. A study in exhaustion and disintegration. My grandfather’s exile echoed there too. The collapse belonged to them, not to me. I was supposed to be the one in control, the craftsman who holds the material steady while the world inside the book breaks apart.

That was the theory. Nietzsche distrusted theories and systems, and so do I, but I still tried to operate under that illusion of control.

In reality, the five or so years I spent working on Turin coincided with a period of growing instability in my own life. Personal instability. Political instability. Psychological instability. I am culturally Jewish, but not religious, and in recent years Jewishness became something exposed again, something lived in public rather than privately carried. It became a condition rather than an identity. There was the unease of becoming visible, the pressure of mass hostility, the moral inversions of contemporary ideology, the righteousness that treats condemnation as virtue. All of that pressed against the book. I could not exclude it.

Nietzsche was part of this tension as well, because he remains widely misrepresented. He is often described as antisemitic, although he held Jewish culture in high regard. It was his sister Elisabeth who hated Jews, and who mutilated and rearranged his work after his collapse, turning him into a mirror for others to project onto. That distortion has never quite disappeared.

A question began to haunt the writing.

Do I protect the book from my life, or do I allow my life to contaminate the book?

By contamination I do not mean confession or therapeutic disclosure. I mean the psychic climate under which a work is produced. Anxiety. Grief. Humiliation. Anger. Hypervigilance. The body under stress. The way fatigue alters judgement. The way exhaustion can make you brutal with your sentences. The way fear can move you either toward falsity or clarity. Nietzsche confronted the same forces while writing his books in Turin as the world around him began to swell and tilt.

At various points I found myself asking whether formal control required excluding this instability, or whether control sometimes meant allowing it to bleed into the work. I do not believe this is a simple either–or question. As with piano playing, there are many right ways, and what is wrong often appears instantly, before you can rationalise it.

There were days when I tried to write as if nothing had changed. Those were often my weakest days, not because the writing was technically poor, but because it felt hollow. A book about collapse written from a position of simulated serenity felt false. The distance was not rigorous. It was evasive.

But the opposite danger was always present. If I loosened my grip too much, the book risked becoming a document of my emotional state rather than a world that could stand on its own. It risked sentimentality disguised as honesty, or self-pity camouflaged as revelation. That possibility frightened me more than anything.

So, the work became a negotiation between these temptations.

There were passages I wrote when my anxiety was high and the world felt newly hostile. I refused to smooth them later, not because they were perfect, but because to alter them felt dishonest. They still trouble me. They are not quite right. But they broke a habit. They stripped ornament away. The fracture became visible and stayed visible. It became part of the structure rather than a flaw.

There were other passages I rebuilt when calmer. The emotion was real, but it had distorted proportion. The sentence had lost balance. Feeling had overwhelmed meaning, and that was a failure I could not accept. Form and content are the same thing, just as interpretation and technique are inseparable in music.

What I feared most was not exposure. It was distortion.

I did not want the book to become narrower because my world had shrunk, or angrier because I was angry, or fragile because I was fragile. But I also could not pretend I was writing from steady ground. Jewishness moved through the work, not as a theme to be announced, but as inheritance, vulnerability, ambiguity, pressure, loss.

Looking back, I cannot claim that instability deepened the book, or that suffering refined anything. Most of the time it simply made the work harder, slower, lonelier.

If there is a lesson, it is provisional. Perhaps we do not protect a book from our circumstances. Perhaps we decide, again and again, what kind of mark those circumstances are allowed to leave. Sometimes the mark strengthens the grain. Sometimes it warps it. The work lies in trying to recognise the difference, or in accepting that we never fully know, and that part of the task is to go on anyway.

I will never be satisfied with Turin, even though it is finished. Valéry wrote that a work is never completed, only abandoned. I understand that now more than I did when I began.

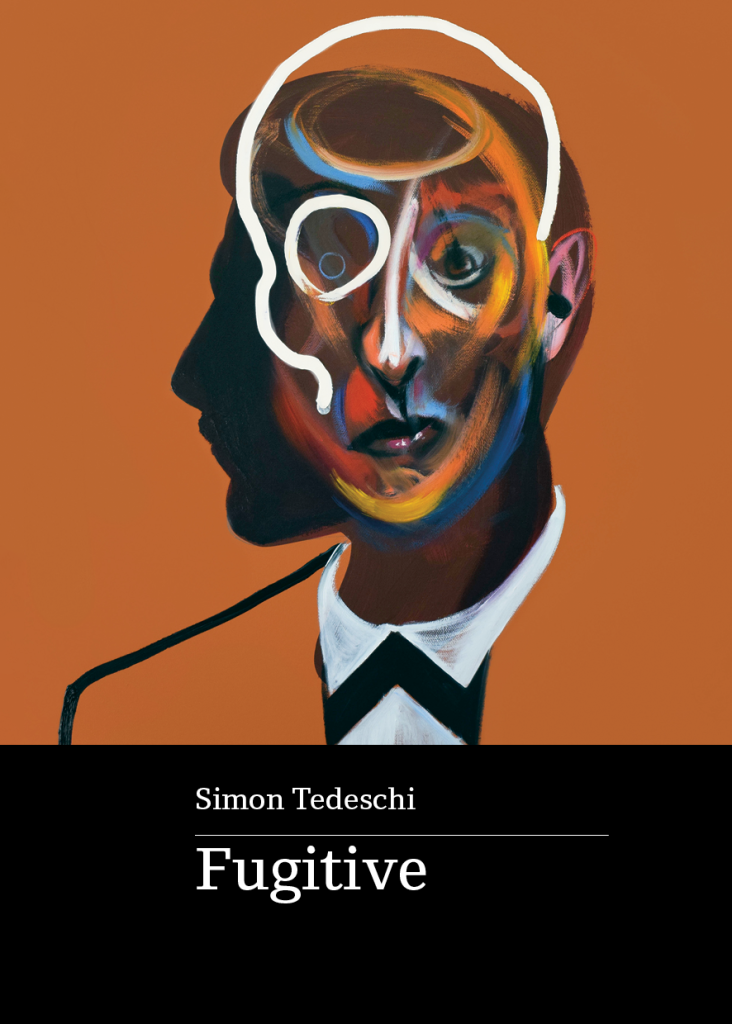

Simon Tedeschi is one of Australia’s leading classical pianists and a recipient of the Young Performer of the Year Award, the Creativity Foundation’s Legacy Award (USA), the New York Young Jewish Pianist Award, and a Centenary of Federation Medal. He has performed as soloist with all major Australasian orchestras and at venues including the Sydney Opera House and Carnegie Hall. His album Debussy – Ravel was ARIA-nominated, and his book Fugitive was shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and the Judith Wright Calanthe Award.

Deeply thoughtful book. So interesting in from Nietzsche was part of this tension as well, because he remains widely misrepresented. He is often described as antisemitic, although he held Jewish culture in high regard. It was his sister Elisabeth who hated Jews to “I will never be satisfied with Turin, even though it is finished. Valéry wrote that a work is never completed, only abandoned. I understand that now more than I did when I began.”

So much self analysis, doubt as Simon was thrust into the public.

Susanne, yes, Nietzsche’s story is endlessly fascinating…

A most eloquent examination of the writing process. And I must read this book now.

I’m also reading Simon’s book now. It’s so good! xx

Incredible! This has completely turned my idea of what I thought a book could be on its head – and indeed the writing process. The idea that a work of the imagination has a “psychic climate” has made me see art anew; as a living thing, shaping us as much as we are shaping the work, coming alive on the page as we create it and then again when it is read… Thank you for such an insightful and moving piece, Simon! Upswell definitely have their finger on the perfect key when it comes to publishing. Listening to your music as I write today… and looking forward to delving into more of your work – written and composed – in future.

What a wonderful response to Simon’s music and writing, Bianca, thank you for this! x

Thank you all for such gracious comments. <3

A wonderful piece Simon. It resonates deeply. I look forward to reading the book.

Arnold, so glad Simon’s words speak to you.

Wow

I’m overwhelmed by this article…

Not just due to the difficulty of the book’s subject, but the writing process – at this terrible time – along with the heady combination of honest vulnerability paired with intellectual plus philosophical challenges.

I found it deeply moving, thank you.

What a moving response, Kassia! Hope you’re ok…