I spent nine years grappling with a manuscript I couldn’t complete. Not because I lacked compelling material. My mother and grandparents had survived the Holocaust; there were dramatic stories of love and betrayal, rescues and buried secrets. But I couldn’t land an opening that set up a singular thread for a complicated, multi-generational family saga. It wasn’t until my tenth year of writing that I realised the problem: I was asking the wrong central question.

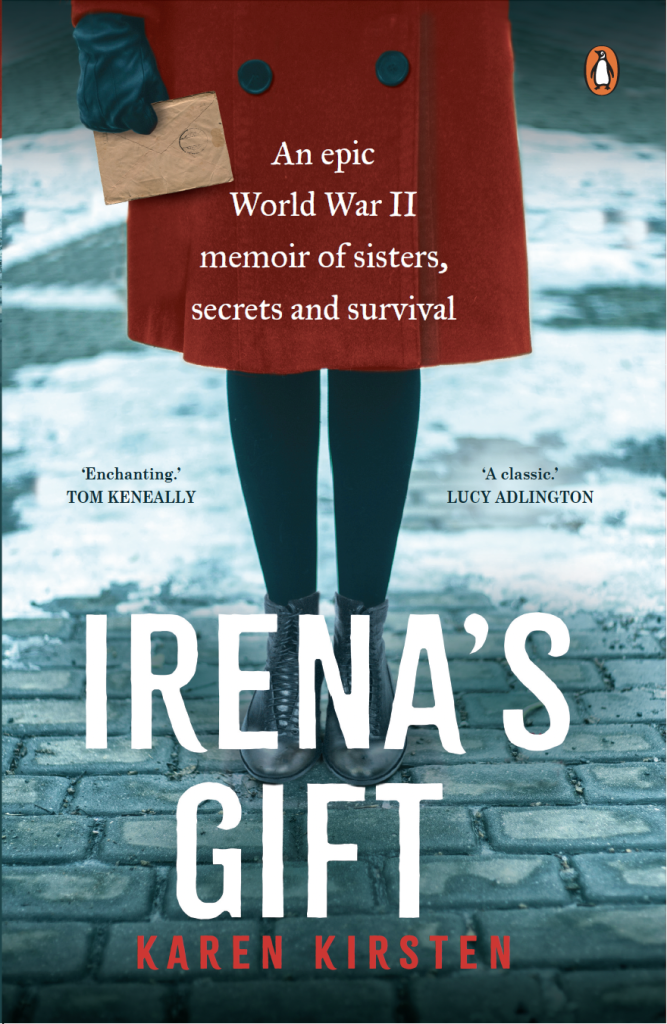

In fiction and nonfiction, the ‘central question’ is the story’s engine. It’s the thread that pulls the reader from the first page to the last. For fiction, in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the central or dramatic question is: ‘Will Romeo and Juliet overcome their family’s rivalry to live happily ever after?’ For years, the central question I pursued was: ‘How did my mother survive a war?’ After I changed it to one that placed me in the story, I finally found a structure for Irena’s Gift that draws readers into narrative twists and turns that lead to a series of reveals. (Judges for a recent award said that ‘it reads like a thriller.’)

I’d never thought of myself as a writer. I’d promised my grandmother, Alicja, I’d write down her story of rescuing my mother in German occupied Poland, and surviving Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, more for my nieces given I had no children. But after I moved to the United States, my leadership career took off. Then one night, a few years after Alicja’s death, I googled her surname and clicked on a link that opened a black-and-white clip of an interview filmed days after the US Army liberated Dachau concentration camp. A man in a striped prisoner uniform stared at the camera, his face pale and stubbled, rutted eyes and brow, his cap frayed. My grandfather, 34 years old, who’d never discussed the war. The same man who’d gamboled about with the child-me on his shoulders. The man who’d played hide and seek, ducking in and out of a retired tram nestled beneath gum trees at Wattle Park in Melbourne.

My discovery of the interview marked a tipping point to finally honour the promise I’d made my grandmother. I quit my job and travelled to Poland and Germany to research my family’s story. I took classes on how to write scenes and develop characters. I read books like Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit, Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, Elena Ferrante’s The Neapolitan Novels andPaul Auster’s Leviathan,and mapped them on butcher’s paper to study how authors build propulsive narratives that keep us turning pages. I completed a ‘shitty first draft’ and took more classes with journalism and English professors at Harvard, resulting in my first published essay––about a Nazi officer who saved my mother’s life.

Yet no matter how many times I workshopped my manuscript’s opening pages, I couldn’t nail an opening dramatic discovery—the inciting incident that sets up the central thread. My story was too complex. With too many discoveries early on, it lacked a clear beginning and felt like four different openings. At a conference, literary agents (in the U.S. you require an agent for publisher submissions) told me I, as a character, was missing from my memoir. I needed to be the protagonist-detective-narrator and a fully fleshed out, flawed character. I needed to be the conduit to my mother’s history.

But I didn’t believe this was my story to write. My mother and three of my grandparents had survived the Holocaust. I had not experienced war. Agents asked, ‘What was it like being raised by these damaged people?’ Redraft, they said. Send the full manuscript when you’re done.

Exasperated, I applied for a year-long MFA level intensive tailored for full-length manuscripts. That was when my instructor, Alysia Abbott, pointed out I was pursuing the wrong ‘central question’.

My mother had always sensed she’d been reunited with the wrong parents after the war. She was short and chubby. They were tall and slim. They’d dismissed her nightmares of armed men in jackboots and of hiding in dark rooms. They adored her brother, but she claimed they beat her. So, to insert myself as a detective-like character in the present timeline tackling a mystery, I changed my central question to: ‘Why did my grandmother appear to hate my mother when she’d risked her life over and over to save her?’

A central question should lead to smaller ones that create cliff hangers along the answer-journey. For example, in the memoir Men We Reaped, Jesmyn Ward tells the story of the violent deaths of five young Black men she grew up with, including her brother. In the prologue she says she aims to ‘understand why my brother died while I live, and why I’ve been saddled with this rotten fucking story’. The central question driving her story is: ‘Why did my brother die?’ Along the way, Ward pursues secondary questions about the roles racism and economic inequality played in these deaths.

I had covered Alicja’s caustic treatment of my mother in my manuscript, but I didn’t make it the primary theme. My new central question led to a new opening scene for Irena’s Gift: me visiting my grandmother with my mother. Alicja is delighted to see me but brushes off my mother and yells at her. I end with a cliff-hanger that sets up the first reveal:

After witnessing Nana Alicja’s spitting insults, my sister-in-law asked Mum why she put up with the treatment.

‘Because she is my mother,’ Mum said pragmatically.

But the problem – as we knew by then – was this was only partially true.

I then moved my original dramatic discovery opening to a later chapter. The reader learns that when my mother was thirty-two, she received a letter from a stranger in Canada who wrote that Alicja wasn’t her mother; that when my mother was one year old, Alicja’s sister, Irena, was shot dead while hiding with my mother in an attic outside Warsaw––Alicja, was, in fact, my mother’s aunt and Irena was my mother’s biological mother.

Secondary questions helped me pace and unpack my big reveals: ‘Why did Alicja despise the man who sent the letter – my mother’s biological father?’ and then ‘How could a father give his daughter away?’ These helped me explore the price of silence across generations and how hidden histories shape who we become.

For memoir, answering the central question is not the same as resolving the plot. In The Situation And The Story, a book about the art of personal writing, Vivian Gornick points out: ‘What happened to the writer is not what matters; what matters is the large sense the writer is able to make of what happened’––in other words, the writer’s ability to interpret, understand, and find meaning within what happened.

So, how do we know when we’ve arrived at the correct central question? For memoir––and fiction––it can take dozens of drafts to uncover what we are truly writing about. Our original question might lead to a different one. I recommend posing different questions and exploring them until you find a central thread that resonates.

While our family history might be interesting to us, unless there’s a dramatic hook and a story arc readers can connect with (e.g. the messiness of family in Irena’s Gift) our stories are less likely to find a publisher. And sometimes it takes a writing community to ask the question we’ve been avoiding all along.

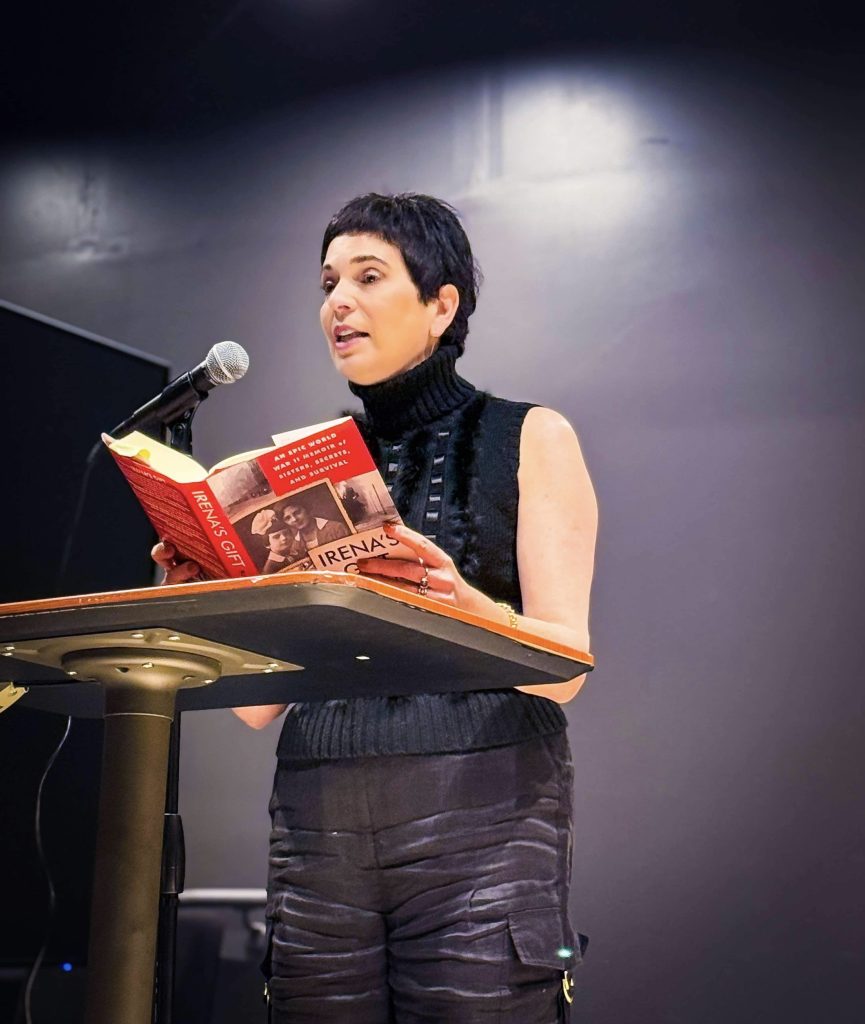

Karen Kirsten is the author of Irena’s Gift, shortlisted for the 2024 Leslie and Sophie Caplan Award for Jewish Non-Fiction, the 2025 US National Jewish Book Award and winner of two Zibby Awards for Best Family Drama & Best Story of Overcoming (US). Karen’s Narratively essay, ’Searching for the Nazi Who Saved My Mother’s Life’ was nominated for The Best American Essays and her writing has appeared in The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, Good Weekend, Salon, Huffington Post, The Week, The Jerusalem Post, WIEZ in Poland, Boston’s National Public Radio station and more.

Thank you Karen for the post and your thoughts on the importance of the need for the storyteller to land on the central question that will hook the reader. As someone who is writing a memoir about a time in my life, putting the ‘I’ front and centre is not really a problem. Even the central question is not that much of a stretch. But then, I am early in the draft stage and I may discover that the central question needs to be reviewed.

I am also writing an historical novel based on a real person. Nine years into the writing and ninety thousand words into a second draft and I’m still wondering what my character’s central question is.

Finally, I like to write longer essays about subjects which interest me and have begun posting work on Substack. Even in short-form storytelling and communication, pause to ask two questions: “What is this really about?” and “Where am I in it?”

Richard, I love how prolific you are as well as adventurous, working across a variety of genres.

Jumping between memoir and fiction is impressive. Keep going, Richard!

Incredible… so inspiring, Karen! I love how you’ve made the story of how you found your way to your book’s central question a compelling narrative in itself. I look forward to learning more about your memoir and essay. Wishing you continued writing success! Bianca

So glad Karen’s story spoke to you! It’s a great book.

Thanks Bianca!

I’m so pleased that I read Karen’s guest post. I’ve been struggling with a second draft of my manuscript by thinking that I knew the central question, but now that I’ve re-thought it, thanks to Karen, I think I’ve been off the mark! Thanks Lee and thanks to Karen.

So glad Karen’s post was useful to you, dear Heather! Thank you for telling us and happy writing

Heather, I’m so glad it helped!

Oh wow. I loved this post. It came at just the right time for me. I was struggling with the introduction to my memoir, and have, with Karen’s help, completely rewritten it. So wonderful! Thank you!

This is just incredible, Peter! So glad it was so useful!

That’s wonderful. Keep pursuing that new question Peter!

Thank you Karen, for your insights and help in nailing that all-important central question. It continues to morph and evade me in my current manuscript. Your experience in drafting a highly successful memoir gives me new courage.

Happy writing, dearest Dina! x

Thanks for the reminder about the ‘central question’. It’s exciting, while terrifying.

Exciting and terrifying indeed 🙂

Dina, maybe don’t look at your manuscript for a bit. Take a break and come back to it and you might find that new central question. Wishing you all the best!