The world we start writing in is never the same one we inhabit years later as we seek to finalise our work and publish. Fast moving global conflicts, political ruptures and the rapid pace of climate change have made this even more apparent. In my experience, even if you are writing about the past, the swiftly changing present matters as it alters your interpretation of what has come before, and the context in which your work might land in the world.

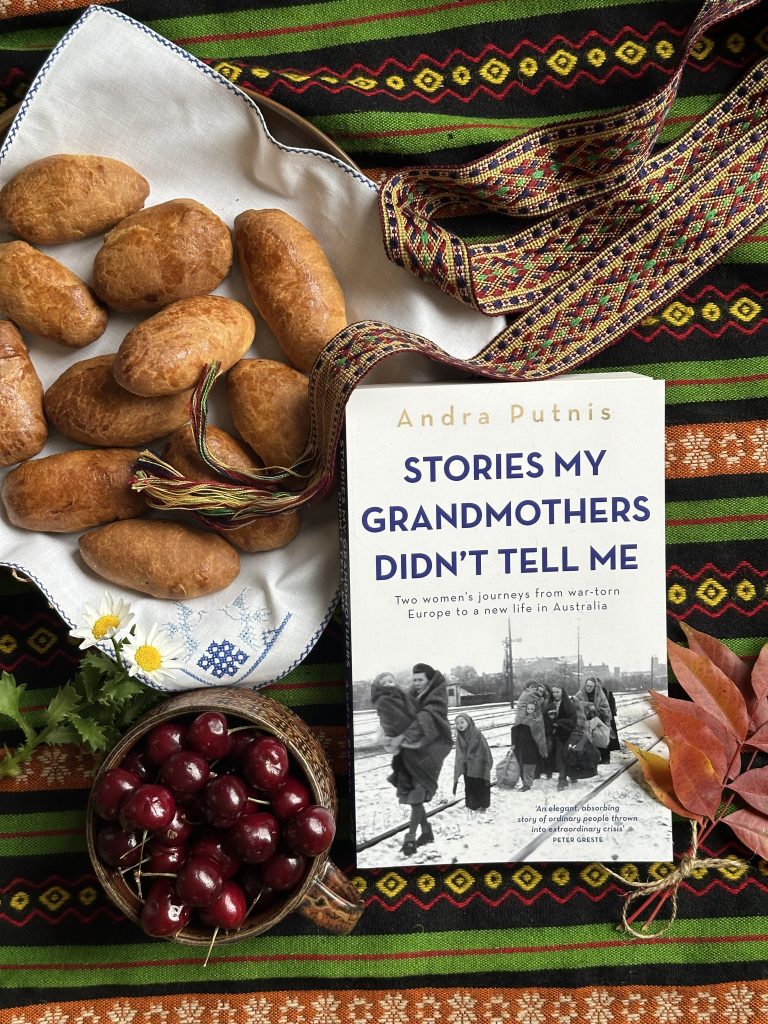

As I wrote countless drafts of my memoir Stories My Grandmothers Didn’t Tell Me, I was focused on looking back to discover how my two Latvian grandmothers survived the Soviet and the Nazi occupations of Latvia during the Second World War and went on to build new lives in Australia.

In the book I surfaced childhood memories of visiting Grandma Milda’s house in the 1980s – a little island of Latvia in the Redhead suburb of Newcastle by the beach:

As children, we’d sneak into Grandma [Milda’s] bedroom on secret missions. Her cupboard was filled with old fur coats, strange woven folk costumes and small mountains of glowing amber. We were half-scared, made breathless by our discoveries, but knew we hadn’t seen it all, hadn’t understood what was really hidden there.

I wrote scenes drawing on the conversations I had with Nanna Alīne during the period of 2004-2021, sitting at her kitchen table in Australia, feeling as if Latvia’s history rushed in to surround us.

I was there, you know! At the very beginning, when the war started for Latvia in 1940. I was there at the Daugavpils Song Festival on 16 June when the first announcement was made. Me, just a girl from Kraslava. There, for that moment… Everyone started to talk at once. I heard one lady cry out, ‘The Russians are coming!’ Too many people were moving and turning to one another. I felt afraid and took hold of Marta’s arm as a horn rang out over the crowd…

Then, in 2022, as I worked to finish my manuscript, Russia invaded Ukraine. Initially, I didn’t think it was my place to write about the unfolding events and steered clear given my research and book were about the past and Latvia, not present day Ukraine. I had already struggled with ethical questions about whether it was right for me to tell particular family stories and worked through these myself and with key family members. I wasn’t sure broadening out to consider new stories, another step removed from my family, was a good idea at this late stage.

However, the invasion of Ukraine sent shockwaves through Latvia and the other Baltic States. It reminded Latvians across the world of the fragility of the independence they’d fought so hard to restore after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It resurfaced fears about how fast the peace and security of people’s homes could again disintegrate – fears that had been held by Grandma Milda even after Latvia regained its full independence in 1991, and until she passed away in 1997. I decided this was part of the unfolding story of my family. I asked myself what Grandma Milda would think if I didn’t address Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and guessed she would think I was being foolish and missing a vital part of the story. I decided the best way forward was to convey what I recalled of my grandmother’s mindset, and face up to my deep-seated fears about what the future may hold:

When I was in my late teens, Grandma Milda often warned me Russia would seek to reoccupy former Soviet countries, including Latvia. Her deep distrust and fear of the Russian state never wavered through all her years living in Australia. I must have absorbed her warnings in some measure. Learning of the invasion of Ukraine, I realised I had been expecting Russia to reoccupy its neighbours in my lifetime. A part of me had been waiting for it.

As the book came closer to publication date, I watched the geopolitical climate in Europe further decline and the rise of dictator-like leaders across the globe. I listened to Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk remark that with Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, it felt again like 1939 in Europe. He went on to warn that people, particularly younger generations, must no longer see war as an abstract idea or something of the past and be open to see that ‘any scenario is possible’.

Tusk’s words resonated with me – they were one of the reasons I decided to travel to Latvia in July 2025 for the launch of the Latvian translation of the book.

At the entrance to the open-air ethnographic museum on the outskirts of Rīga, sits a stone statue of a softly bowed head. The words underneath are ‘kas senatni pētī, nākotni svētī’, roughly translated as ‘those who study the past, honour the future’. As I stood there gazing at the statue, any remaining doubt about the importance of linking the past and the present evaporated.

As I now reflect, I feel I learnt the important lesson that our work can improve when we shift timelines and perspectives. An everchanging world is the backdrop to our work. This is not something to rail against. We can’t re-write again and again as events unfold, but we can stop along the way and ask ourselves some interesting questions:

How has the global context changed since I set out to write this piece?

In my case, the context had changed very significantly and I felt I needed to acknowledge and write about this while still conveying the past and the perspectives of the characters at the beginning of the story.

Does thinking about this question help me better understand the place and time of the people in my work?

For me, the question helped clarify the critical role the passage of time was playing in my work. The timeline for my book ended up to be 1913 to 2023. I was able to follow strands of history and see them culminate in the present.

What might be revealed by drawing a narrative arc from the past to the present…and even possible futures?

In following the arc of my grandmothers’ lives through from the Second World War to the present, I found the true heart of my book. It sharpened my understanding that freedom from oppression and the precious states of peace, democracy and the rule of law are not inevitabilities to be taken for granted. If war happened to my grandmothers, why couldn’t it happen to me? War descends on ordinary people, as it is happening now to many across the globe. As I reflect in the final pages of the book:

Nanna [Alīne] taught me nothing less than what it means to be human, to earn the grace and wisdom that come from surviving darkness and celebrating light.

Andra is a writer and the Artistic Director of the Canberra Writers Festival. Her debut book, Stories My Grandmothers Didn’t Tell Me, was published by Allen & Unwin in July 2024 and by Zvaigzne in Latvia in July 2025. It received the Canberra Critics’ Circle Award in 2024 and was shortlisted for ACT Book of the Year in 2025. Andra was awarded a Highly Commended in the 2025 Calibre Prize for her essay ‘The Art and Atrocity of Disaster Scenario Planning’, published in The Australian Book Review, September 2025.

It’s a very important narrative. The past informs our future. And on that note, wishes & a message of peace to us all.

Thank you, dearest Margaret! And same to you x

Andra, thank you for your generosity and courage in sharing this story, and the past and present threads that entwine our lives – what a brave, inspiring and sweeping narrative it is! Your words will resonate with me, so many moments for deep, sobering reflection here, on where we have come from and where we are headed. Wishing you both (Lee and Andra) much peace and creative energy for the new year – Bianca

thank you for your wonderful wishes, dearest Bianca, and for your ongoing support. I hope 2026 will be a year of beauty, inspiration and indeed peace for you too x