Last year an editor I’d worked with made what I initially thought was a puzzling remark about my writing. ‘I find your Russian worldview fascinating,’ she said. The work-in-question had nothing to do with Russia. Plus, while I’ve written in two different languages, neither of them is Russian – my mother tongue. Nor have I ever considered myself to be a ‘Russian writer’.

I spent my first 12 years in what used to be the Soviet Union, but never quite felt I belonged there. I was a child of a Jewish mother, born in her native Siberia, but my father was a Ukrainian Jew and when I was six we moved to live in his hometown, Odessa. At the time Ukraine was a Soviet republic and home to many Russians too; the boundaries between them and Ukrainians were fuzzy. However, being a Jew was a clear peril wherever you lived, as my family experienced firsthand, so I’ve always felt ambivalent about my Russian heritage. Not only as a Jew, but also as a refugee of Communism and, later, as an appalled observer of ‘Putinism’ starting from far before the horrors of the Ukrainian invasion.

After we fled to Israel, I published three books in Hebrew. When, later, I moved to Australia, I moved to writing in English. In both languages, I’ve written about my years in Russia and Ukraine, and some of my fiction is set there, but I never felt I was writing like a Russian. I thought of myself as a ‘passionate outsider’ writing about a place that has indelibly imprinted on me its beauty and its brutality. The country, as I remembered it, was a feast – its operas, vaudevilles and books, Siberian snowstorms, Odessa’s sun and salt. The country was a wound too, in so many ways – with its oppressive regime and regime-mandated antisemitism. I bled, but as a writer I didn’t think I was of that country’s flesh.

One recent night and the editor’s remark suddenly made perfect sense. I was watching the second season of The Great, admiring the chutzpah with which the Old Russia there was deconstructed and remade. In one memorable scene there, Peter, the Russian emperor, reluctantly follows an ancient custom: in anticipation of his child’s birth he’s digging two graves – for the mother and for the baby. This way, another character reassures him, if they die you are prepared. And if they survive, your happiness will be enhanced. Peter protests – why would you want to so horribly spoil what should be a joyous time? Because this is Russia, his men, gathered around him, say laconically. Then, as if to end the discussion, they burst into an utterly depressing song. The digging goes on.

For the record, there was no such custom in Russia (although it suffered no shortage of bizarre traditions…). But to my point, watching that scene made me grasp what my sensitive editor already knew. True, with my myriad of cultural and other identities, a true Wandering Jew that I am, I’m forever a passionate outsider no matter the language or subject matter I choose. Still, there are Russian traces in my worldview and hence on my pages – not in a geopolitical sense, but rather they have something to do with that famous metaphysical, but so physical to me, so embodied in me, concept of ‘Russian soul’. That famous Russian sense of fatalism mixed with the absurd, probably nurtured by centuries of suffering under despotic regimes, captured precisely in The Great’s hilarious scene

It must be no coincidence that tragicomedy has always been my preferred genre to write and to read. Whether I intend so or not, my pages are always tinged with melancholy, often of the morbid kind, as well as with laughter in the face of this morbidity. In other words, in whatever I write there is always a group of ridiculously overdressed grown-up men huddled together stiff like choir boys, singing an utterly depressing song while somebody is digging a pre-emptory grave…

Thank you. What you may still have to offer is not obvious, but more than likely a surprise when it comes. In the meantime, you are bringing out what is in others what they not realize they have. Congratulations.

You’re very kind, Rob, as always. Thank you!

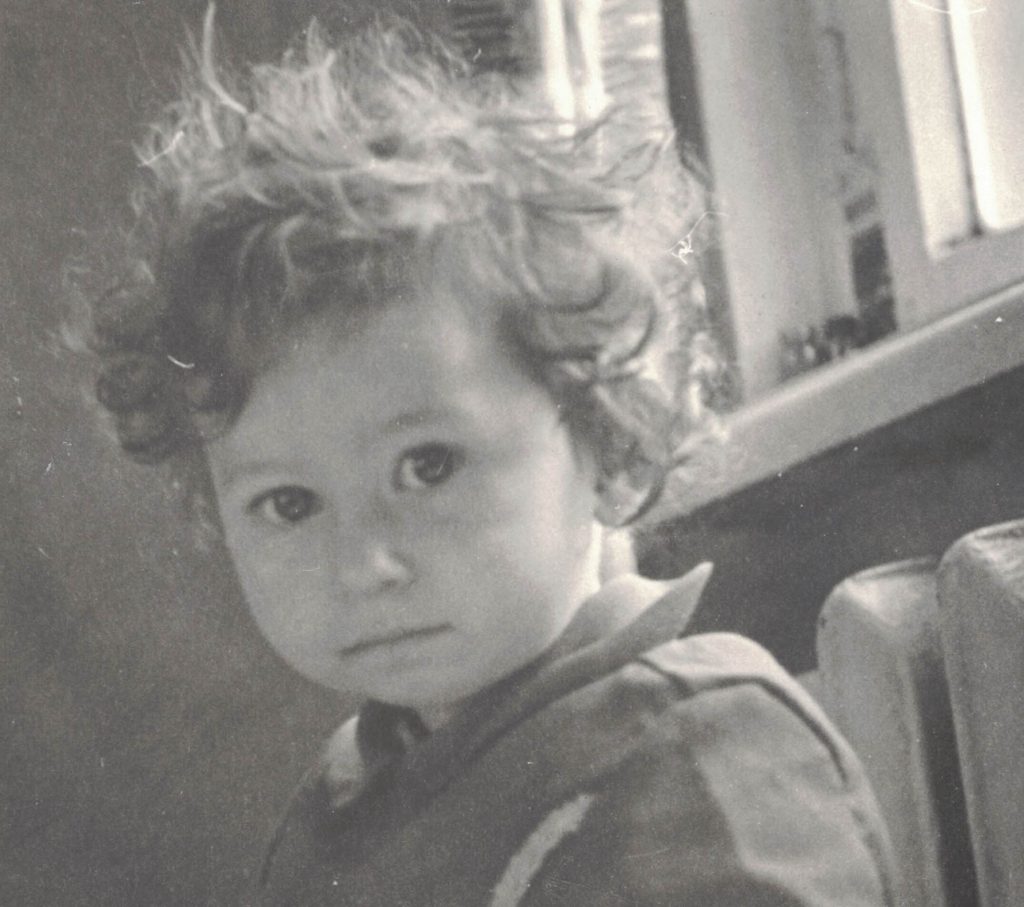

This article, when you talk about the ‘Russian soul’ led me to ponder about our ‘writing soul’ if there is such a thing. I suspect there is and it develops or is present so subtly that it is not obvious to us until perhaps someone catches a glimpse of it. I also love the photo of you as a small child, exquisite and knowing. Thank you, Lee.

Thank you, dear Heather, and thank you for sharing your thoughts. I love this idea of a writing soul – maybe it’s what we define sometimes as ‘writer’s voice’, who knows…

A compelling image that reminds me that hope and despair are often fellow travellers.

Thanks for another gem.

Frank, your words mean a lot – thank you!

Although I am not knowledgeable on the topic of a ‘Russian soul,’ i also felt this quality in your writing. Reading your short story ‘The Taste of Mango’ reminded me so much of Chekhov. Fascinating reflection Lee. Thank you.

Anni

Dearest Anni, but you do sound knowledgeable… Thank you for your beautiful response to my work; you know I am a fan of YOUR writing.

I also find your worldview fascinating—it is quite different and refreshing—although I would probably not call it Russian. And I love your emotional honesty that shines through this article as well as it does in your other writing. Always a huge pleasure to read your words.

Edita, thank you! It’s so meaningful to hear this from you – having loved your memoir so much!

I love the picture of you as an innocent child already touched by the dark soul of your Russian heritage. My own grandparents, great-grandparents and many great-greats before them, came from Russia and Ukraine, some from the Pale of Settlement. Although I have never been to those countries I’ve always felt a strong spiritual connection to them. Do you think this is genetic? Thank you Lee for your inspiring book, ‘The Writer Laid Bare’, and for your constant encouragement to other writers.

Many thanks, dearest Dina, and now that I know your heritage I think – no wonder I feel kinship to you x

Dear Lee,

I think your intellectual breadth and your sense of history mark you as “of the old Russia”. In your wonderful instructive book on writing you refer back often to the historical greats in literature. When I think of other writing craft books I admire by American writers, Canadians, Australians, and some English authors, they are more likely to reference their own narratives and the oeuvre of contemporary writers. The Writer Laid Bare had me re-visiting Tolstoy, Proust and Flaubert, as well as pan-global contemporary greats.

Shannon, many thanks for your response! I’m so glad you and I share the passion for reading broadly, across times and continents.

Lee, I recently copied this quote into my notes, and refer to it daily at the moment. The soul is elusive, but this makes me think. ‘His wounds now bear scars, and those scars dull all feeling. You may see that as a flaw, but I assure you, just as the body will protect what was damaged, so too will the soul.’ — Steven Erikson

this is lovely, Jen, thank you x

Nothing but Irish coming from this end of the internet. But I love your depiction of the Russian soul, and how timely at present. I’m sure the Russian soul heavily influences your writing soul. Write on, Lee.

Thank you, dear Margaret, and I suspect Irish soul can be very useful in writing endeavours 🙂 x