I was separated from three of my children, the first at the end of the 1960s when I was seventeen. A familiar story in those years. Unmarried mothers were often hidden away, and babies adopted shortly after birth. An agreement was signed that we would never contact our children again. Giving our babies away to ‘proper mothers’ was considered a sign of how much we loved them. Later we were branded as the kind of women who could give away their own child.

I lost the two children that followed in an international custody dispute. I did not have the financial resources to challenge the case and the fact that my first child had been adopted was cited as evidence I was unfit for mothering. I did have some access to my daughter and son. It was the reason I moved to Australia from Canada, but I had little say in their care.

My daughter grew to love art and writing, and in her late teens we formed a bond over this. Another thing we shared was a form of muscular dystrophy, catastrophic for her as she progressed from a wheelchair to the point where she could no longer sit up. In my case, the symptoms were mild, a slight weakness down one side. It took decades for the genetic connection between us to be made.

Later my daughter developed cancer. Due to the muscular dystrophy, she was unable to have the tumour removed. Her stepmother and father fought on with natural therapies. Some thought they were mad. I followed their instructions to the letter but couldn’t fully engage in this battle. Instead, I worked on plans to take my daughter to Paris, the city that inspired her writing and art.

I have been a writer for over thirty-five years. A journalist first, who like many journalists would rather write creative works. Over the years I wrote three novels but sabotaged myself constantly when it came to getting them into print. I wanted success for my daughter first. I felt my genetics and ‘shameful’ choices had eaten her life. And then she died, and then I went mad and ended up in the battlefields of France trying to make sense of it all. I couldn’t have gone to Paris. I felt I would have been stealing that from my daughter too.

I never intended to write a memoir, but I did – and not the sort of memoir that most publishers want. The events have all the makings of a grand narrative, but I wrote a slim volume structured as a collection of letters. Why?

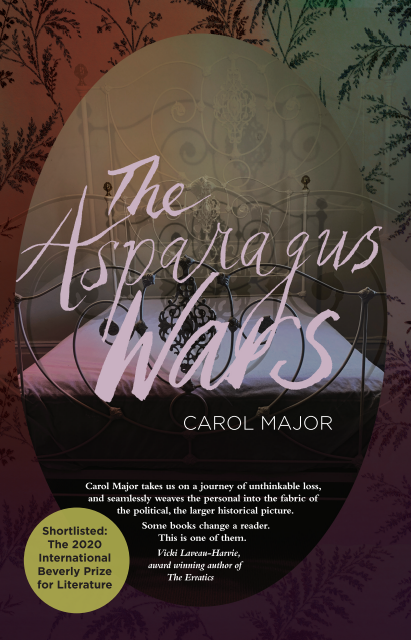

One of the first things I asked myself when I began crafting The Asparagus Wars was who was telling the story to whom and why? There were challenges in the why. I could tell the story from a place of anger. I could tell the story in defence. I could create a lot of heat but not necessarily illumination. And there was also an overabundance of content. One could get lost in the mire. What was the central question?

The battlefields of France are filled with too much content. Even after more than a hundred years, people dig up grenades, helmets, and bits of barbed wire. In Verdun the ground is so thick with bones every time a tree falls skulls and femurs come up tangled in the roots. There is no way of identifying who was who.

My own life had been a war, the carnage spread over decades, and like any war it was shaped in the language of binaries and moral righteousness: good mothers versus bad mothers, the intelligence and counterintelligence strategies played out in family courts; the certainty of positions on how to save a life so that one feels they can defeat anything, even death.

In his wonderful poem, From the Place Where We Are Right, the great Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai compares rigid certainty to a hard trampled yard and describes how doubt and love can break up that ground and offer possibility, movement, and the ability to come together. I did not want to write from a place of defence that trampled events and narrowed vision to confirm a particular stance. I wanted to see it all, show it all: the contradictions in character among everyone involved. People were sometimes cruel and at other times kind. I did not want to cement them into friend or foe but instead show us all being terribly human.

In the French battlefields I saw the binaries inherent in concepts of winner or loser, liberator or oppressor cracked open. I wandered through military displays of cooking utensils, inkpots, and pens. Ink pots and writing implements were found all over the Marne, almost as common as artillery and bones. The soldiers, many no more than boys, had been writing letters and poems trying to make sense of the terrible paradigm of war. I realised their despair at being driven onto the battlefield was central to the story I needed to tell too. My tale was more than the custody dispute, more than having my first child removed, more than seeing my daughter lowered into a grave; it was what drives us to treat each other in this way.

The other question I needed to answer in framing the structure of this book related to the ‘who was I speaking to’ aspect of the story. I suddenly realised in my anguished journals I’d been speaking to my daughter all along. It was her ears I needed to reach.

I didn’t tell my daughter the full story of the custody dispute when she was alive, because I felt it would place another burden on her. But in death my daughter could hold the ‘all-ness’ of things. This is why I chose the intimacy of letters to her. There was nothing that I would hide or defend. It was my own bones laid bare.

As for finally pushing a manuscript into the world, my writer-friend Jessie Cole asked, ‘why this one?’

I mumbled something about wanting to be part of the conversation among published writers.

She raised an eyebrow in response.

I was silent for a moment, twirled the cup of tea I’d been sipping and then prodded my neck.

‘Here,’ I said. ‘Here and here. I feel as if I’ve been choked.’ A rush came over my body as I said those words realising how long I’d been too frightened to speak, frightened for my children, frightened I’d be judged, shamed, and punished again. But I didn’t care now. If I didn’t speak into that silence, I would die in it and all I had witnessed and tried to make sense of would go with me.

Carol Major was born in Scotland, later completed her education in Canada and now lives in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, Australia. Her short stories and poems have been published in Canadian and Australian journals, and she has authored numerous articles in health care, social policy and urban design. Her memoir, The Asparagus Wars was recently published by Es=Press, an imprint of Spineless Wonders publishing. Carol is an alumni and valued mentor at Varuna, Australia’s National Writers House.

I adored this memoir.

Susan, thank you, and thank you for getting its heart.

Beautiful post – Goosebumps!

Dear Effie…so pleased the intention touched you. Warmest Carol

I’m lying in a bed on a cold, misty autumn morning at Varuna as I read this post, tears dripping onto the pillow. Your words reach out and speak to me just as I ready myself to revisit my stalled memoir. Thank you Carol, for your honesty, and for your memoir which touched me deeply.

Oh Annie, have the bestest time at Varuna.

Such a moving post. I must read Thr Asparagus Wars. Thanks for posting.

Dear Anne, thank you so much for your response and to Lee for creating this blog.

This is so honest and beautiful. What a tribute to your daughter and yourself.

Hello Carol: I have followed you as much as possible through our lives. The brief time we were connected through high school was like a drop of water in the ocean of our lives but, for some reason, was deeply important to me. I have not yet been able to purchase your book but am determined to do so. Somehow this post hit close to home and I immediately thought “who’s life have I been living”. Be gentle with yourself my friend. You have already survived.

Christine! Heavens to find you here. We both have survived dear heart. Be gentle with yourself too.

What a role model you are for others, like me, who write from a position of finding a voice! I look forward to reading your book, Carol.

Dear Anne. All good thoughts for your own writing and that unique voice.

This is so beautiful, Carol. I can’t wait to read your book, and thank you so much for your help guiding me with my own words, permissions, and self-compassion on the writer’s road.

Laurie it has been my absolute pleasure. Warmest thoughts Carol

Beautiful, Carol. So passionate and true. Nourishing to the soul.

Dear Patti, thank you for championing so many voices. You are a treasure.

Thank you for this inspiring story, dear Carol. I hope I can show the same courage in my writing. I love that you quote from Yehuda Amichai the wonderful Israeli poet who speaks truth so powerfully. It was great to meet you at Varuna and I look forward to more of your words of wisdom.

Thank you Dina. Isn’t he the most wonderful poet xox

Wow, Carol. This is an incredible post. Thank you for sharing your story, and for the reminder to write what matters to our hearts. Much love and all the best for your memoir in the world.

Thank you Kim. I’m glad it touched your heart.

What a beautiful and deeply affecting post, Carol. I love your writing, and keep coming back to your words. Your drive to “show us all being terribly human” strikes a resounding and reassuring chord. Thank you for sharing. Much love, as always.

Dear Barry,

Thank you so much…and in the same way your own book ‘Broken Rules’ took me to a felt and known place.

Your book remains with me. I read it slowly, felt every emotion. I recall our meeting in your open kitchen when you critiqued my work. I noticed your daughter’s art and you talked about her. I sensed her presence as well as yours as I soaked in every word of the Asparagus Wars.

Anne, how lovely. Thank you for this.

Your book contains the “allness” of the best literature. We humans, in the current of our lives, with all our foibles and yearning possibilities. Thank you for your beautiful memoir, Carol, and this wonderful post about your structural choices.

Shannon, so glad you love this memoir, I do too! So much is captured in so few words…

Thank you Shannon. There are so many choices in writing a manuscript, aren’t there? So many possibilities. But eventually it tells you what it wants to be.