Reading and writing are intertwined activities for me. I am drawn to reading and writing for the same reasons: to engage in a story, in different worlds, in extraordinary words. I can’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t reading a book, or when I wasn’t creating a work-in-progress of some description, even if that work was a hand-made comic book or greeting card, or some fan-fiction.

My childhood wasn’t always easy. My parents married very young, and they were divorced before I was one. I tagged along to whatever my mother was doing. She was a musician and took me to rock concerts in places like the Riker’s Island Women’s prison, or smoky clubs. I was often left to my own devices there with paper, crayons and pens to keep me occupied. One thing that helped ground me was that no matter where we were, I always got my bedtime story. Both my parents were good readers, and the bedtime sessions were often extended, with a theatricality that involved me joining in this creative reading too. There were different books at my mother’s and father’s houses, but both of my parents owned books by Maurice Sendak.

My mother liked to read me Chicken Soup with Rice. Sometimes we would sing it together, channeling Carole King. I always took the once/twice refrains (“happy once; happy twice”). When my mother wasn’t reading the book to me, I’d pretend to read it to myself long before I could actually read. It was only a small step from saying the words I’d memorised, miming my mother’s finger against the text, to recognising the words on the page. It was only one more step to copy the words into a notebook, moving naturally from reading to writing. The repetition, the simplicity, the sense of nourishment and safety, made Chicken Soup with Rice a perfect primer. My maternal grandmother referred to her famous chicken soup as Jewish Penicillin and though she used barley rather than rice, the book always made me think of her soup, and the way it would warm me. I sometimes made up my own refrains as I walked around the house chanting: “oh no, oh once” or “hello cat, twice”, an early foray into creativity, spurred on by the ease at which that book became part of my mental chatter.

At my dad’s we had In the Night Kitchen, another Sendak book with a culinary focus, but this one –objectively – is a scary one. Micky falls into the night kitchen where giant bakers mix him into dough. The situation appears to be grim for Micky, and Sendak’s bold illustrations emphasise the nightmarish quality of the story. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that Micky turns the situation around with gumption and ingenuity and not only saves the day, but gifts us all with cake in the morning. My dad put on a full Oliver Hardy accent for the stodgy bakers, and I always got to be Micky, shouting “I’m in the milk and the milk’s in me”, which I was encouraged to do differently every time. Micky’s nakedness caused a stir with puritanical groups (Sendak’s books are often banned and considered ‘inappropriate’ for kids), but not in our house. To me it felt like Micky’s triumph was one of self-acceptance coupled with freedom from the straightjacket of cause and effect (another type of clothing): in the book’s universe you can fall down or up, little boys can be mistaken for milk and milk comes from giant bottles in the Milky Way. As with all Sendak books, the child is the one who has agency over hapless big people or monsters. Then, In the Night Kitchen is a book where creative solutions, like turning dough into planes transform a frightening situation into something safe and nourishing like cake. When I was a child, Micky’s creativity in solving the problem of the milk spurred me to create my own hand-made versions of Sendak’s story (with “Maggie” instead of Micky) using vibrant hues, exclamations, sound effects and rhythms.

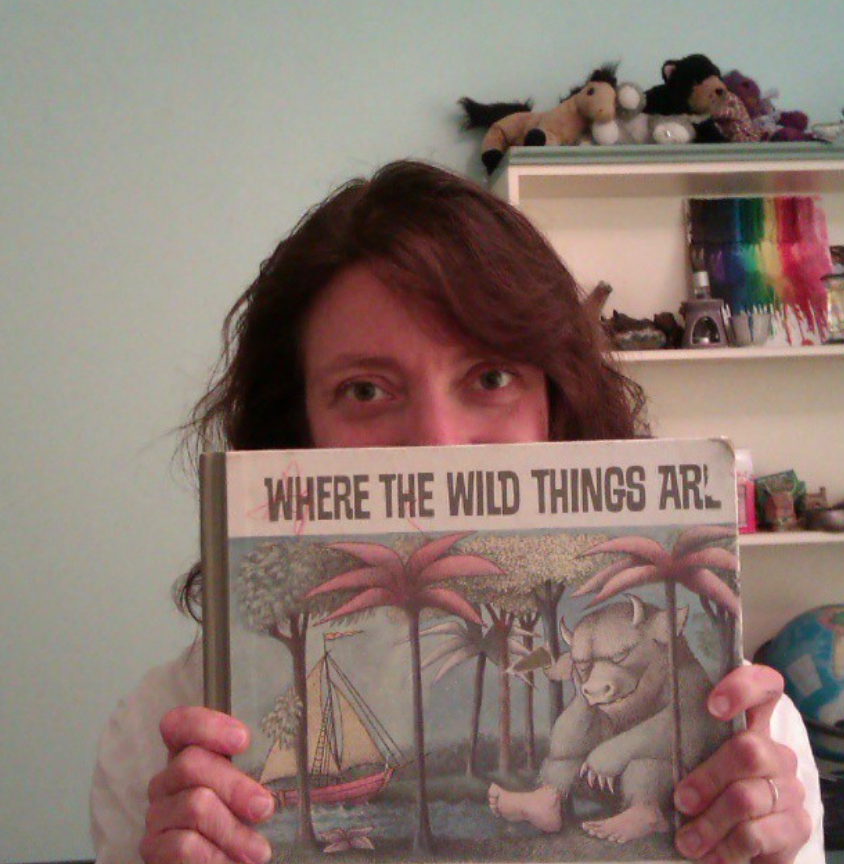

Both parents had my favourite Sendak book, which might be my favourite book of all time – Where the Wild Things Are. My mother would read it with dramatic flair, but it was always my turn when we got to the wordless ”wild rumpus”. I know there are parents who think that the protagonist Max’s behaviour is too naughty and the monsters are too frightening. But for me, the book is the opposite of frightening. It’s yet another Sendak story about the power of creativity, where you’re the hero of your own journey, facing down the secret and nameless terrors we all carry and using that fear to create something wonderful. Max’s kingdom of ferocious monsters who might “eat him up” because they love him so much feels true, and his magic trick of staring those monsters down is one that I find underpins much of my creative process.

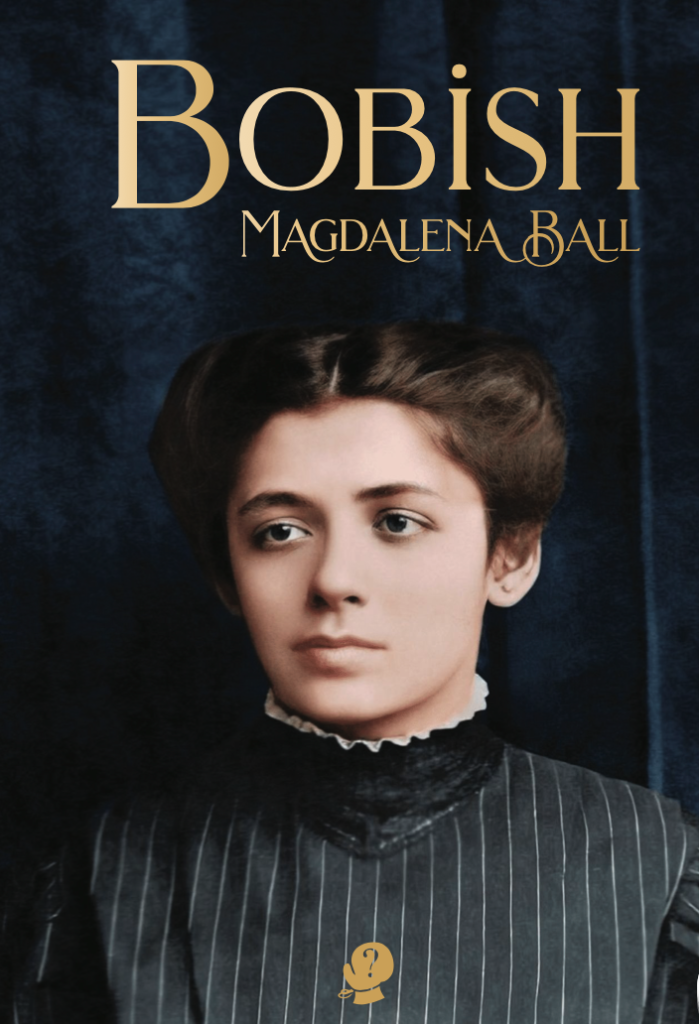

Enacting the ”wild rumpus” was one of my earliest exposures to the idea of making use of fear, frustration and confusion as the basis for a creative response from which there is always a way back. For example, in my latest book, Bobish, a verse memoir that traces my great-grandmother’s migration from the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe to the US at the age of 14, I knew I had to engage with family trauma that encompassed the anti-Jewish pogroms of the early 20th century, and later the Holocaust. I imagined my grandmother, who used to sing to me in Yiddish, using her voice as a way of dealing with the darkness her mother carried and I wanted to use my own voice to link through her to her mother and find the source of the pain she carried. Writing like this felt to me like a kind of magic trick, like Max’s trick of staring into the Wild Thing’s yellow eyes without blinking..

Sendak’s books seem to tap into the primeval joy and terror of childhood – something deep-seated in all of us. Re-reading these books with my children gave me that same shiver of excitement and a sense of possibility that it did when they were read to me so many years ago. I know this is the same catalyst that I draw on when I sit down to write. As Lee Kofman says in The Writer Laid Bare, the ’best writing is an expedition into the unknown, the urgent, and the uncomfortable’. For me, this is the place I’m always drawn to – using that discomfort to get a little deeper into these dark spaces of the past and transforming them through connection and empathy. To my mind, it’s the lesson of Micky and his airplane kneaded out of dough, or Max with his paper crown. We are all wild things at heart.

Magdalena Ball is a novelist, poet, reviewer and interviewer who grew up on the lands of the Lenape in the US, and currently lives and writes on Awabakal land. She is Managing Editor of Compulsive Reader, and her work has been widely published in literary journals such as Meanjin, Cordite, and Westerly, along with many anthologies, and is the author of a number of fiction and poetry books, most recently, Bobish, a historical verse-memoir from Puncher & Wattmann. Find out more about Magdalena at http://www.magdalenaball.com.

Lovely explanation (showing your writing talent)! I read those books to my children and first graders not realizing some people didn’t like them. Carole King’s song was frequently played and enjoyed. We did not know enough to be scared, I guess. This brought back rhyming memories.

Bobish is a wonderful book that should be required reading.

Thanks so much, Carolyn. I really appreciate your wonderful attention. Our early books really do shape us. xx

Read another good reading experience in an outstanding series. Thank you.

thank you, dear Rob!

Thanks Rob, this is such a terrific blog (and Lee’s own book is superb).

What a wonderful introduction you had to the world of words and the joy of reading, and being read to. The warm intimacy of a child reading with a parent is a memory you treasure for ever. Sad to say thousands of children – state wards growing up in institutions- never experienced that joy. Some never had a book of their own. In extreme cases some never learned to read. Magdalena, your piece is a powerful reminder of that great loss.

Frank, thank you for your moving response to Magdalena’s post! I know you’re speaking from experience and I feel for you. But what an accomplished writer you turned out to be despite the tough beginnings of your life. You know I love your work.

The wonderful childhood memories linking reading and writing brought my own four year old life back to me. My father, striding into our small working class home and I had to choose which hand. There was always a book.

And Christmas Eve before I started school- the nails being knocked into the wall. My own blackboard. So intense is that moment when the letters I was drawing on the board translated into sounds- into words.

Thank you Magdalena and Lee for this beautiful post. xxx

Love your stories, dear Susan! Thank you xx

Thank you Magdalena for your evocative piece on the power of story. Your beautiful book ‘Bobish’ is transporting me to the time of my own forebears in the Pale of Settlement. Through haunting verse you tell the story of so many of us. ‘Bobish’ is a treasure.