For some years I’d entertained a shy little dream to write a book loosely based on this blog you’re reading right now. At the same time, the oh-so-familiar refrain of ‘who are you to advise others on writing?’ kept playing in my head. So apart from some brief, non-committal remarks to my husband I never discussed this idea with anyone. If I was superstitious, however, I’d have said I must have manifested my desire to a rather attentive universe, because this is what happened in 2019. My dear publisher, Jane Curry of Ventura Press, called a meeting – to discuss some book idea she had in mind for me, she said. I thought it would be another anthology to follow the two I’d already edited for Ventura. But Jane said, ‘You know this blog you’ve got. We would like to see a book from you on this topic.’ Oh man…

However, even in my exalted state I knew I couldn’t simply build a book from a blog. My posts about the rigours of the writing life were random bones that did not add to a comprehensive, coherent creature. I had craft-focused posts about such matters as dialogue and character writing; practical tips on publicity; humorous posts about various hypocrisies of the literary world; poetic flights of fancy about the mystery and wonder of the writing process. This suited a blog, but a book needs some unifying principle to hold its pieces together as well as to know which of my posts belonged, at least in parts, and which didn’t, and what gaps I needed to fill.

Worse, in the face of the avalanche of books on writing out there, what could I possibly contribute to the existing conversation? We live in the time of Writing Resource Cornucopia. Myriad works offer writing advice and exercises; sometimes even recipes for creating the next bestseller. I have my reservations about some such books. I am particularly skeptical about following some fixed steps to create a story, as doing so puts writers at risk of producing formulaic works. Plus, there is no such animal, in my view, as one creative process fit-for-all. And yet, I am the proud owner of a bookshelf crowded with books on writing.

The books I collect, those which have meant the most to me and are my constant practice companions, are written by authors who share my view of writing as both art and vocation. They are more discursive than didactic, and they help me to remain inspired – not in the fluffy way of ‘connecting to your inner muse’, but by pushing me out of my comfort zone, by provoking me to think in more complex ways about writing and life in general, and sometimes just by sweeping me off my feet by the sheer beauty of their prose. Francine Prose’s Reading Like a Writer, Aharon Appelfeld’s A Table for One and The Paris Review’s volumes of interviews are among my favourites.

Thinking about what kind of family of writing books I wanted my book to belong to helped me to focus. I wanted to write a book that is practical in the sense that it has some clear suggestions about the process and craft of writing, but I also wanted it to be personal, reflective in tone, focused on the creative process and on the quality of writing as opposed to on how to get published. Plus, I wanted to discuss the so-called ‘life-work balance’ for writers. More precisely, to consider how writers may live lives conducive to their art but without obliterating themselves for its sake like some of the greats advised (Rilke, I am talking to you!). And yet… there was still no clear centre to my book, no specific angle.

With a book deadline looming, I proceeded to re-organise my pantry, plant roses in my garden, bake cakes and record ideas for other books I may write one day. This hiatus lasted for some weeks, bringing joy to my husband and children, but increasing my anxiety. Nevertheless, there is something to be said about the merits of procrastination, when your brain isn’t anchored to a project but roams free. On one such desolate day I had the idea to browse through my old journals, the ones I wrote during my first years of living in Australia. There I came across the following entry:

‘Nonesty’ is when your typing fingers are not in sync with your memory, or your heart. Nonesty is when you describe what you are supposed to feel. It is when you are so focused on finishing a work that you don’t ask yourself questions, because they are a waste of time.

Nonesty was a word I coined at that time, the time when I grew so despondent about my writing that I had to make up a word to describe what was wrong with it. To say that what I wrote then was ‘dishonest’ didn’t feel right, because it didn’t contain outright lies. But my words emanated a subtler stink, one more difficult to get rid of. I sinned more by omission than commission. There wasn’t enough honesty in my prose.

What I mean is that I airbrushed whatever I wrote. I smoothed the edges of even mildly controversial topics. And I skimmed only the surface of my characters’ minds: Does she love him or not? He is a loner because he had a difficult childhood. I failed to explore the ambivalences and gradations inherent in romantic love (she may love him a little and need him a lot) or that a solitary nature is likely to be formed by a mix of factors (is he also an introvert with a rich inner world?). I wasn’t sufficiently in touch with the complexity of human thoughts and emotions. Or, as the editor of my then-latest book put it in an email: ‘You’ve taken your readers on a fascinating tour through the main streets of your novel but foregone visiting the hidden alleys.’

On top of that, in the process of changing countries and languages I had lost touch with my gut. Being self-aware is always hard work, or at least it is for me; however, I struggled even more when I had just begun writing in English. In a language not yet embedded in me viscerally I found it harder to unpick my feelings and experiences into their molecular components. And if I wasn’t sensitive to my own complexities, how could I have the insight to describe those of others and reflect meaningfully on others’ anxieties — their idiosyncrasies, biases, conflicting desires?

There was a mix of reasons why this happened at that point of my life, but one of the main ones was seemingly paradoxical – because I was already published. A book of short stories I’d written in my early twenties was uncomfortable and probing; it examined the poor choices otherwise decent people make – to plagiarise another’s work, betray a friend, commit violence. I wrote those stories because I was possessed by them and wanted to exorcise them from my system. I didn’t really believe anyone would publish them, so it was easier to write as Jonathan Franzen thinks writers should: ‘like a firefighter, whose job, while everyone else is fleeing the flames, is to run straight into them.’ But as I entered my thirties, more published and more self-conscious, I was no firefighter. Assuming that what I wrote now was more likely to be read, I felt exposed and frightened to say things that are not said in polite society.

My lack of deep reflection extended into the writing process itself. I sort of ‘forgot’ that difficulties in writing are a natural part of creating; every challenge appeared to me as a catastrophe, yet more proof that I had no more books left in me. I wasn’t connected to my shifting needs – the conditions I needed to work at my best in my new country in my new language. I wasn’t even clear on whether what I was trying to write was what I really wanted to write or thought I ought to.

I went on struggling like this for four years. Or rather, this was more than a struggle: it was a crisis, which I now understand to be a full-blown writer’s block. It began dissipating only when I finally admitted to myself what I wanted, yet feared, to write about – my experiences of non-monogamy. And even when I began writing a memoir about that, it took me a while to approach my subject with honesty and nuance. By the time I finished that book, I came to appreciate the critical importance of self-awareness, deep reflection and moral courage for writers – three concepts I now fit under the umbrella term of emotional honesty.

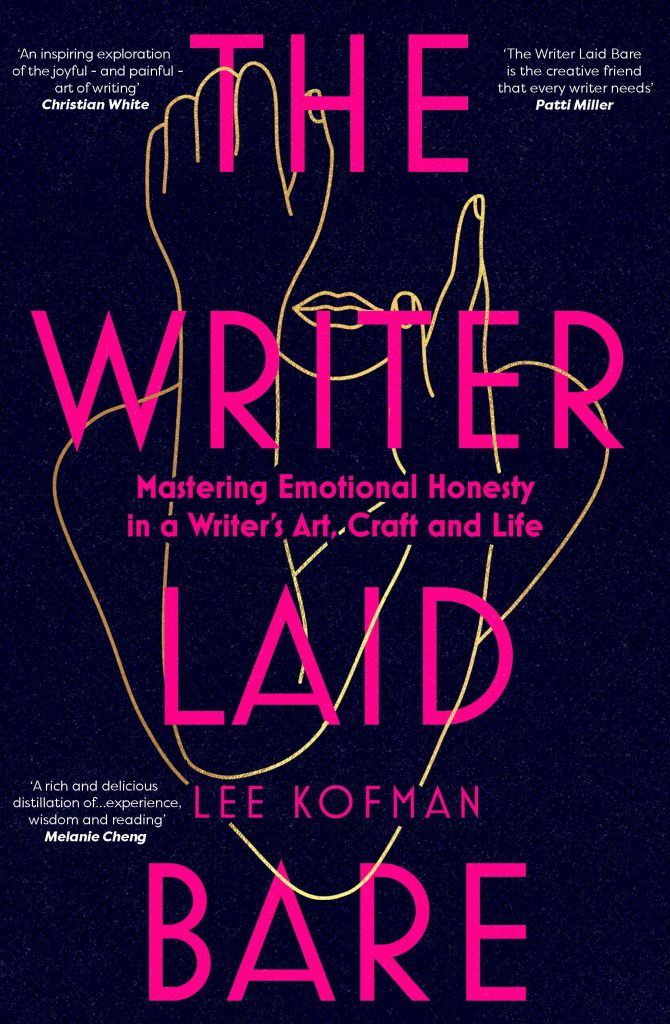

Revisiting my journals made me think of how often I’ve worked, as a teacher or mentor, with writers who – for their own unique sets of reasons – have grappled with issues related to emotional honesty, seeking more clarity about how their individual writing process worked and striving to create honest, bold works. Finally, that metaphorical light bulb went on and I knew through which lens I wanted to discuss writing. I’d write the kind of a book I once needed myself, as I strongly suspect timely advice would have spared me years of wallowing in despair. If only someone back then had pointed out that my difficulties weren’t a sign that I couldn’t write; that struggling with authenticity, candour and self-understanding is something writers must do, often throughout their entire lives. Not all of us naturally know how, or dare, to write like firefighters. So I closed my baking book, opened my laptop and typed the sub-title of my book-to-be: Mastering emotional honesty in a writer’s art, craft and life.

Note: This book, I’m happy to share with you, just came out last week into the world.

This is the book I need right now! I have second book ‘somethings’ and the rawness and emotion evident in my memoir is not emerging now. Thank you Lee. I did greatly fear it was a case of ‘no more books in me’ but you have given me some hope.

x

Susan, you’re such an accomplished writer and it’s humbling to know that you’re struggling too right now. I hear you. Thank you for your beautiful words and may your writing flow and flow x

I’ve been greedily gobbling your book on the art of writing and authenticity. I feel like you are speaking directly to me, or at least to the writer I wish to be. I’m viewing present and past manuscripts through your wise words & experience – AHA!

Shannon, hearing this means so much, especially that you’re a beautiful writer! Thank you very much.

Hi Lee,

Congratulations on your new book! I love your work and writing style. Your writing is inspiring.

You have amazing ability to write so beautifully.

Well done!

thank you so much, Rosemary!

I’m going to purchase the paperback, because I know that I will want to refer to it again and again. Congratulations, Lee!

Many thanks, dearest Anne! I’ll love to hear your thoughts on the book once you read it x

Mazeltov Lee, on this wonderful new book, a gift to writers everywhere! I look forward to gaining guidance and wisdom from its pages.

Dearest Dina, thank you for your generous words and I hope your own writing is going well!

Fabulous, Lee. Congratulations! Absolutely can’t wait to read it.

Michelle, big thank you! x

Thank you for this blog post, Lee. There is much I can relate to. I can’t wait to read your book.

Karen x

Thank you so much, Karen, and please let me know your thoughts on the book when you read it x

Your words really resonate with me, Lee. Returning to Australia 8 years ago after 47 years away, I’m still trying on my new persona and identity, still filtering what people say and how they say it.

Lilian, wow, an absence of 47 years… There is a book in it by the sound of this! And thank you.

Love it, Lee. I do think there is a big battle between what one wants to say, and what you think ‘polite society’ might want to hear or sanction. Rock on with your encouragement to writers.

Margaret, thank you! And happy writing to YOU x

I needed to read this today. Thank you. I’m off to buy the book. In part, to support, selfishly – it may be the very thing I need to get me out of this funk.

Oh wow, Rhiannon – thank you! And please do let me know if it was of any use to you. Lots of luck with your manuscipt!