I was a backpacking 21-year-old when I got off a ferry from southern Spain to the port city of Tangier in Morocco with four Australian friends. Once on land, we had to run the gauntlet of what we called, simply, ‘hassle.’ Finally, we chose a tall young man who matched our steady pace for a few blocks, whispering in my ear, ‘Better one mosquito than one thousand.’ He wore a cream linen suit and lots of gold rings. His eyes were the bluest blue. We trusted him.

He set us up in the Hotel El-Muniria where William Burroughs had written Naked Lunch, then took us to his home and introduced us to his parents and siblings. His sisters hennaed our hands and feet in traditional designs and slaughtered a hen in their backyard, for the best tagine and couscous we’d ever tasted, eaten with our hands from the communal pot. After a few days we guessed he was looking for a way out of Morocco with a quick marriage to one of us; he really didn’t care which, but we didn’t either as we lounged on floor cushions and drank his mother’s teeth-achingly sweet mint tea.

He also asked if we wanted to visit Paul Bowles. Bowles was an American expat, composer turned novelist, who lived in the old city with his young lovers, male and female, smoking hashish and majoun (cannabis jam) and holding court. The year before we’d arrived, the travel writer Paul Theroux had interviewed Bowles for his book The Pillars of Hercules. Kerouac, Isherwood, Ginsberg and Burroughs had also made the pilgrimage to Tangier to see the writer. But we didn’t have a clue who he was, so we went to the Kasbah instead.

It wasn’t until I got back to Sydney with a suspected dose of TB that I decided to read Bowles’ most celebrated book, The Sheltering Sky, called by some the most perfect novel of the twentieth century. And I fell in love. I re-read the book, took notes. I watched Bertolucci’s (disappointing) film, which featured a cameo by the author. Bowles’ boldness as a writer taught me how to approach the process of my own work and helped me forge my burgeoning identity as a young writer.

‘I’ve never been a thinking person,’ Bowles told a Paris Review interviewer. ‘One part of my mind was doing the writing, and God knows what the other part was doing. I suppose it was bulldozing the subconscious, dredging up ooze.’ I liked this explanation of the writing mind. I felt as if that was what I had been doing naturally since I was a child, ruminating, dreaming, sometimes brooding. It took the pressure off having to produce a set number of words every day (which I’d had drummed into me from all the how-to-write books I’d consumed), having to be overly analytical about my writing philosophy, and having to prove myself to the writing world. Bowles also thought that ‘whatever one writes is in a sense autobiographical, of course. Not factually so, but poetically so.’ I felt that instinctively too, and still believe it.

The Sheltering Sky also affected how I write. Set in the French Algerian Sahara, it follows the travels of bored, disaffected, independently wealthy American couple Kit and Port and their friend Tunner, who drift aimlessly deeper into the desert on the eve of World War Two. Everything that can go wrong eventually does, until at the end of the book Kit is a widow, alone, traumatised, sexually abused and mentally disturbed, wandering further out into an unknown horizon yet again.

Something in Kit’s unravelling anti-narrative resonated with me deeply. Bowles’ view of human nature was pragmatic, without sentimentality or fake morality. Theroux called it an attitude of ‘fascinated disgust.’ This stance mesmerised me. The disintegration of Kit’s sense of self, of a fixed identity, her loss and displacement, shaped many of my views on my own position as a writer with my in-between, liminal identity, neither Greek nor Australian, belonging nowhere and everywhere. The female protagonists of two of my novels, The Glass Heart and Bone Ash Sky, and my novella, Intimate Distance, are similar to Kit in their extreme, skinless sensitivity coupled with bouts of recklessness and self-destruction. They are always on the cusp of something unnamed, something sinister or terrible or unthinkable. They revel in their abandonment of expectation and duty – to themselves, others and society at large.

Bowles’ dark and spare prose in The Sheltering Sky, with its austere, hallucinatory beauty, has stayed with me for decades. His book taught me the power of harnessing metaphor in intimate physical detail and the way in which psychological states can be delineated with the most subtle of gestures or gazes.

The Sheltering Sky also sparked my love for ‘dangerous’ travel after that first backpacking trip, a curiosity for strange and wonderful places and cultures. Bowles famously said, ‘I wrote in bed in hotels in the desert.’ When I travelled for the research into my 2013 novel Bone Ash Sky, that’s exactly what I did in the desert border towns of Syria, Turkey, Lebanon and Armenia.

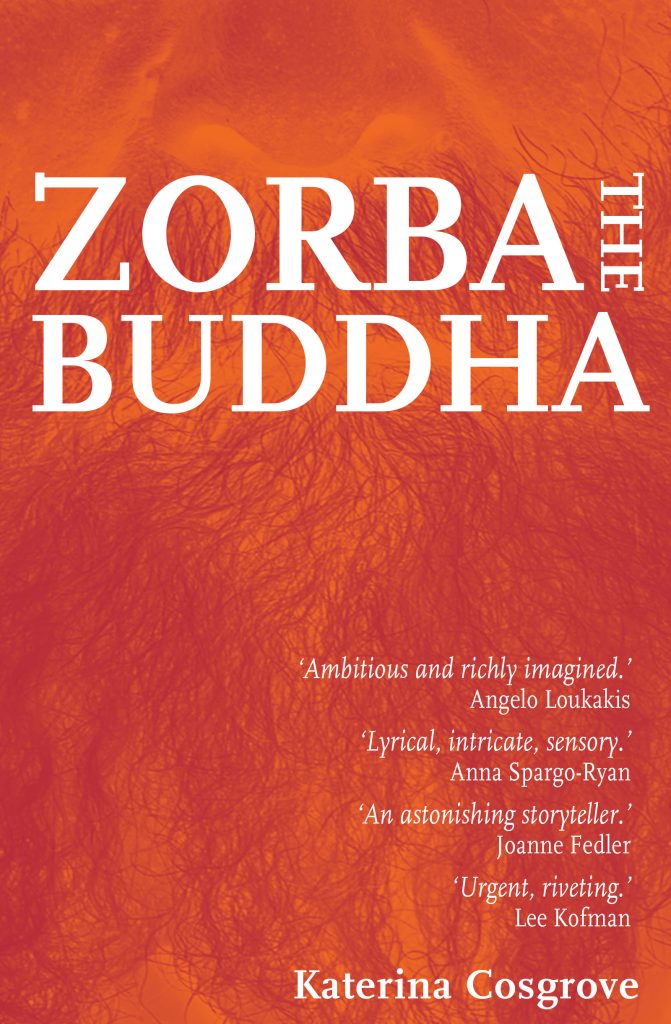

Bowles examines the void beyond our Western idea of ‘civilisation’, beyond thought, beyond right and wrong. This last point is the most important in my understanding of myself as a writer right now. A writer must cultivate the courage to write about anything, including betrayal, cruelty, murder, war and genocide, without judgement but with cool observation and compassion. Bowles’ lessons have endured. When writing my latest work, the novella Zorba the Buddha, my challenge was to chart the demise of a guru responsible for suffering and death among his disciples with a dispassionate, dissecting eye, without taking sides.

Bowles said, when asked about what his message was in The Sheltering Sky, ‘Here’s my message. Everything gets worse.’ I wouldn’t go so far as to say my own books are wholly influenced by this theory, but in my many peregrinations through cults, war, genocide and relationship breakdown, I’ve come to think he may not be far wrong. Here’s my message. Things get a whole lot worse before they get better.

Katerina Cosgrove has been a bookshop owner and university tutor. She is the author of The Glass Heart, Bone Ash Sky and the prize-winning novellas Intimate Distance and Zorba the Buddha. Katerina has written for Al-Jazeera, The Independent, Sunday Life, SBS Voices, Island, Daily Life, ArtsHub and The Big Issue and has been co-judging the Nib Award for Literature since 2014. Katerina also writes obituaries at Live Life Twice.

Katerina, I love this and will always love you and your writing. ‘Skinless sensitivity’ …yes, know that place well. Thank you for these insights. Thank you for your your informed imagination, your restless intelligence, your own maroon heart. Thank you for reminding me of these things.

You are so eloquent my friend. I have learned so much from you in these past years.

Yes, read Bowles, and had an impact. I’ll be in Tangier next month. Then Lesotho. Hope to write in hotels. Read also Tangier by Josh Shoemake. Good read.

I’ll definitely read it Roderick! Keep us posted on your travels and your writing.

Thanks Katerina for this inspiring post, turning many tired old writing maxims on their heads (forget the daily word count, cease analysing your writing, trust the unconscious). I intend to re-read Paul Bowles’ work for more inspiration.

Thanks for your comment, Dina. Trusting the unconscious process is the only way to go for me. Reason and intellect can only get me so far!

This is great. I like your new slant, Lee, because it allows people to discuss their own work, but go beyond to discussing why on earth we would do it in the first place. Thanks, Katerina.

Margaret, thank you! And really all the credit is due to Katerina, for how she interpreted the brief. I hope your own writing is going well, dear Margaret.

Thanks for reading my musings, Margaret. Sometimes I wonder why I keep doing it!

Inspired writing and homage to Bowles. Bravo KC!

Thanks, J mou! Jealous you’re over there right now writing in border towns and hotel rooms x