For as long as I can remember my fascination with the lives of others surpassed the usual level of curiosity. This need to understand other subjectivities struck me early and, since it was not shared by my friends in quite the same way, I pursued it mostly in secret. On the bus to school, I would find myself observing the faces, clothes and manners of my fellow passengers, musing about the work they did, their homes, their families, imagining entire worlds they may or may not have inhabited. But always, the most pressing question: what on earth were they thinking about right now as I stared at them?

I came to Australia when I was nine. I was focused on learning English so I watched copious amounts of TV thinking this would help. I didn’t read fiction until my late teens. Then, once I started reading avidly, it hit me like a lightning bolt. Finally, here was a form that validated what I had thought was an unseemly absorption. In novels, I was able to gain access to lives beyond my own. I was both in thrall and enthralled, until eventually I embarked on the enterprise of creating my own fiction.

Daring to enter the minds of my characters was both thrilling and intimidating. As a Korean-born writer, could I depict authentically an older Anglo-Saxon woman in rural Australia in the 1960’s as I did with my first novel?

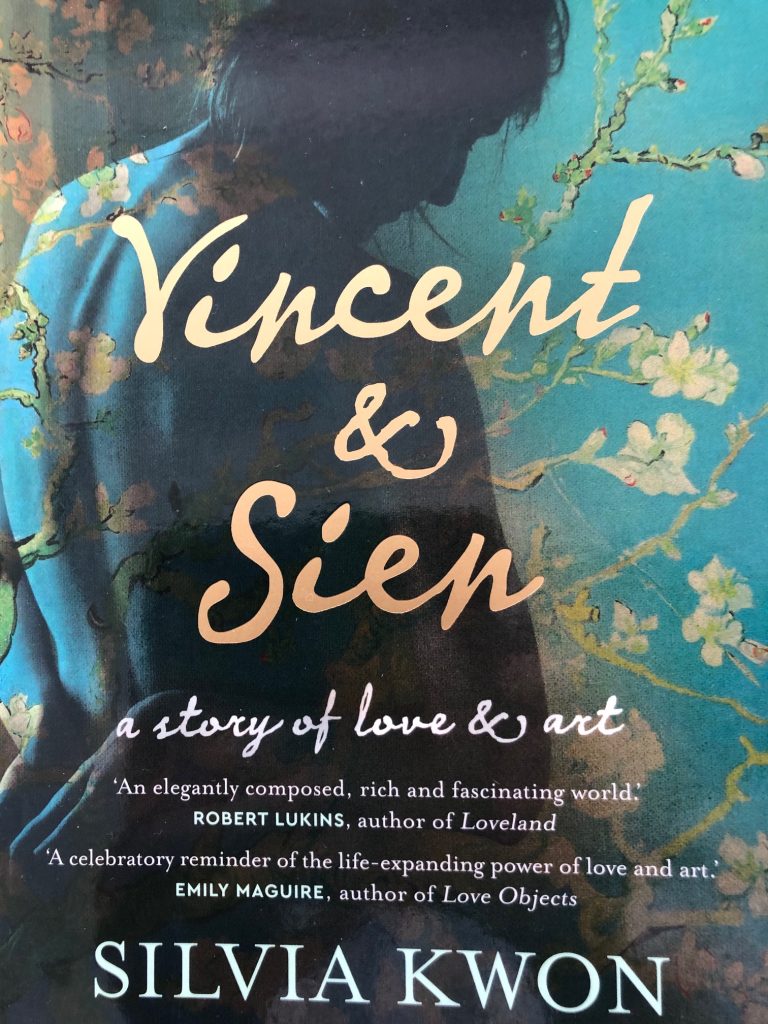

And with my recent novel Vincent and Sien, – a street-walking prostitute in The Hague in 1882?

Can I really assume the voices of these women so removed from my life? How and where would I find their voices?

*

When I first heard about Sien Hoornik, the Dutch prostitute and Vincent van Gogh’s lover, in an audio recording of his letters at the Van Gogh Museum, I immediately wanted to know who this woman was. It struck me that, contrary to my expectations, the artist known for his turbulent life and temperament, at some stage had experienced something of a domestic life with a young family. Quite ordinary, with its inevitable tedium and familial dramas. As a young struggling artist, he pursued not only painting but a home life with a woman well below his social rank, and one who, with her sordid trade, broke all the rules of his respectable, genteel upbringing – a fact he took delight in.

This little-known story was a far cry from the usual image of Van Gogh as the lonely, neglected artist, a tortured soul painting feverishly alone. Like many hagiographic accounts of artists’ lives, his suffering was ardently promoted at the expense of other subplots of his life, which included this brief but intense period of eighteen months that Sien and Vincent spent living as lovers, during which Sien proved instrumental to his development as an artist.

This hidden story tugged me hard.

I wanted to know what happened between them. More specifically, I was curious about Sien, about her experience of living with the renowned artist. Did she fall in love with him or was it simply an economically beneficial arrangement for her? How did she cope with the vast social chasm between them? With his volatile personality? His esteemed family?

There was only one person who was able to record their story: Vincent. But he was both a witness and a party. A learned gentleman, he wrote eloquently to his brother Theo about their relationship while she could neither read nor write. But like in any doomed love story, there were always going to be two divergent perceptions. And despite Sien’s lack of education, Vincent’s letters attest to her strong personality, her keen intelligence, her ability to provide him indispensable support. It was clear she was no wilting flower but a formidable figure in her own right and her version of their story, largely unlit and silent, was always going to be very different to his.

Yet, as much as I wanted to write her story, I was hesitant about bringing her to the page, this woman who was not simply a fictional invention but who had actually lived. I felt a sense of responsibility to her story I had not had with my previous, completely fictional characters.

I approached the task with some trepidation. Keen to discover the ‘real’ Sien, I sifted through the historical material. In time, I accepted that Sien’s story would always be my interpretation, my representation. As Hilary Mantel argues, historical fiction is always going to be ‘a subjective interpretation of history.’ Similarly, it could be argued the unfolding of history itself is intrinsically subjective in nature, the same event experienced differently by those involved. Vincent’s near-daily reporting of their time together, as told to Theo, was always going to be strictly his version.

*

Though I initially went in search of Sien, I ended up finding her in me. As I learned more about her through my research, I intuited we shared much common ground as women, and mothers. Brought up in a migrant household where we didn’t speak English, I felt an affinity to her outsider standing. Sien was born into the lowest of the social classes in a society circumscribed by strict social hierarchy, hemmed in by lifelong, grinding poverty that forced her to walk the streets. She bore three children before she was thirty, with another on the way when she met Vincent. Intimate as I was with the demanding experience of childbirth and its physical toll on a woman’s body, it was not difficult for me to sympathise with her hard-luck story.

The more I researched Sien’s life, the more my trust in my writing and in what I was discovering grew. It was there, in the learning about slum-life in The Hague in the 1880’s, in the horrendous statistics of stillbirths and prostitution, in the tumultuous eighteen months they shared together, and – most importantly – in the undeniable gaps of Vincent’s account of their affair that I discovered the echoes of her thoughts. I could hear her incredulity when he suggested they run away to Drenthe together, despite his well-to-do family denying him support if he stayed with her and therefore the impossible odds of their relationship surviving in the face of this. I soon found myself not only agreeing with her refusal to accompany him but cheering her on. Predictably, Vincent’s version of the ending of their love affair ebbed and flowed with the self-interest of any lover rejected, laying the blame solely on her.

I took reassurance from the writer, George Sands, who wrote: ‘Our minds are built on common architecture – that whatever is present in me might also be present in you.’ The very reason why we still celebrate the works of Shakespeare. Why many old works of art have continued to resonate to new audiences, speaking across centuries. And why I was able to find the confidence to forge ahead with my telling of Sien’s story.

For a little while, I agonised over whether I had got it ‘right’. But I had to accept that this was the best I could do with the material available to me. As Hilary Mantel suggests, a writer of historical fiction must contend with the imperfection of history, the gaps, unreliable witnesses, in short with ‘what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it, a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth’.

But I was extremely fortunate. For I had more, much more than that. A vast number of letters written by one party. They, with the work of examining the remnants ‘left in the sieve’, enabled me to tell Sien’s side of the story.

Silvia Kwon is a Korean-born writer living in Melbourne. Her first novel was The Return (Hachette Australia). Her second novel, Vincent & Sien,

was released in 2023 (Pan Macmillan Australia). It has been translated into three languages.

Fascinating story. I can’t wait to read this book.

I think you’d love it, Sandra.

Thank you for this thoughtful reflection and revelation about interpreting the characters of others. As a sociologist I appreciate the historical backdrop – the political, cultural and social specificities – of people’s lives that inform individual, social and cultural identities.

I appreciated also the comment that authors may dare to create characters, even those from different historical eras, since we all share an underlying cultural architecture, at least at the level of pan-historic human values, including quite contradictory emotions and standpoints.

Thanks again. I will read seek out more of your writing.

Thank you for your response, dear Karen, and it’s also great to learn a bit about who you are and what you do.

Thank you. This is a very helpful article.

So glad you liked it, Peter!

Thank you, Silvia – I was “in thrall” and “enthralled” with your beautiful account, a “story within a story” and thoroughly enjoyed learning about how you came across Sien. It’s the stories in between, in the gaps and silences, that reverberate the strongest, protest the loudest through history, and your quotes throughout are brilliant and so well considered… I look forward to reading and rejoicing in more of your words! – Bianca

Bianca, thank you for your thoughtful response! I highly recommend Silvia’s novels.

‘ … that whatever is present in me might also be present in you.’ I love this George Sand quote. And you’ve done a beautiful job of describing your process and affinity with Sien. Well done.

So glad Sylvia’s post spoke to you!

I loved this article. From your “unseemly absorption” and interest in people when still a nine year old to then discovering books in late teens that allowed you to indulge, indeed wallow in this form, then you, almost unerringly to write yourself.

You have conceded that this is the best you could have done when trying to find the core of Vincent Van Gogh’s prostitute partner, the epicentre from where she operated from in that relationship, mainly through his letters to his brother Theo, but also through recognising what George Sands said who wrote: ‘Our minds are built on common architecture – that whatever is present in me might also be present in you.’

Rubina, thank you for engaging deeply with Sylvia’s post!