It is strange to consider one’s earliest male literary influences as a short story writer when one was not, at least initially, influenced by their gender. Well, I say, I wasn’t particularly influenced. There was, however, a writer who in time helped me define how men could write in terms of emotional breadth and scope, as opposed to how they so often did. His name was Etgar Keret. He didn’t really fit the canon, and thank heavens for that; If I’d read the books I’d been told to read instead of Keret, I might never have known there were men out there just like me, in search of a way to acknowledge their vulnerability and tenderness, as seen, felt, and at times, still desperately avoided by my chosen gender.

In my first few years of writing, many female writers shaped my grasp of the literary craft. I was inspired by the humour in Melissa Bank’s fantastic A Girl’s Guide to Hunting and Fishing and the dry, sardonic voice in Lorrie Moore’s collections, Self-Help, Like Life, and Birds of America. That same year, I stumbled into the arms of Alice Munro (in this case, The Bear Came Over The Mountain) and had to pick my heart up from the floor.

I also read male writers at this time, though none hit with the same emotional heft. Hemingway’s The Old Man and The Sea taught me about writing taut prose but not all that much about writing as a vulnerable, empathetic man. Carver’s stories carried a more recognisable fingerprint of trauma and loss. Still, aside from ‘Cathedral’— an early signal flare for where I might head when I felt brave enough to do so— they were struck down by a certain world-weariness that did not reflect where I was in my mid-twenties.

I wanted to explore masculinity in my work and felt intellectually stimulated by many other male writers, from Peter Goldsworthy to Robert Drewe to Peter Carey and JD Salinger. They revelled in confronting, often disturbing imagery, the stuff of nightmares, and now and then, found genius insights into the stuck and forever flawed male psyche.

The common message among those writers seemed to be: ‘As an author and a man, this is how you keep control. One must present an efficient, vicious story that will stay with your reader.’ A vulnerability was irrelevant or inconvenient when one was busy trying to be insightful. And, aside from the occasional gut punch from a story like Goldsworthy’s ‘The Kiss’ or a book as stark and striking as Andrew McGahan’s Praise, contemporary Australian and American male literature didn’t move me emotionally.

By twenty-seven, I was nowhere near the self-aware, emotionally literate writer I now am. However, I was ready to begin to explore what ached deep down inside of me, beneath my presentation as a strong and independent man. And so it was that a friend and fellow writer gave me his copy of The Nimrod Flip-Out by Israeli author Etgar Keret in late 2004, and I found my heart just in time.

While Keret was succinct in his writing, he seemed similarly curious to find out why he had kept his feelings guarded for so long. He examines this perhaps most poignantly in his story, ‘Your Man’. I won’t spoil the ending. All I’ll say is that there’s something fundamentally masculine and heartbreakingly familiar in how the story’s protagonist smashes apart a once-treasured fort and sees, too late, how he’s left himself exposed to the elements.

I thought a lot about Keret in the stories I wrote from 2004 to 2009. I wondered if Keret had come out feeling lighter, having written stories such as ‘Your Man’, ‘Fatso’, and ‘One Kiss on the Mouth in Mombasa’, where he makes himself vulnerable. Whether the act of being so authentic in his work bled into his real life and how he approached the world.

It was heartening to think I wasn’t alone in caring so much about authenticity and vulnerability. It felt profoundly consoling to believe I, too, might be able to write recognisable and lovable male characters as opposed to the more brutal, grittier men I so often encountered in Australian literature but rarely met in life. Keret also taught me to trust in any metaphor that might best encapsulate a complex emotional state. His stories had some weird shit going on at that— try logically unpacking a girlfriend who turns into a fat, male slob each night and you’ll run into problems. Still it’s perfect for conveying men’s sometimes superficial attachment to a woman’s waist rather than their character. Keret’s work offers two more fundamental lessons for any writer:

- We must never settle for a simple character when a more complex one is waiting beneath the surface, and

- The story ends when it ends. Continue your story after that, and you’re not valuing your reader .

Eventually, I found my own fresh metaphors and thoughts, unlike those I’d previously expressed. Sometimes, in a story of mine like ‘The Butterflyfish,’ Keret’s prints were all over my words. Not thematically, but in the imaginative scope. You find tiny parents, pseudo-angels, or dogs that come back from the dead in his stories; his work so often seems to say, ‘If it works then do it, whatever “it” is.’ In our worldviews, however, we’d often differ. I would, say, lean into hope and see stars glinting up in the sky where he might instead see an angel plummeting to earth.

Keret eventually wrote a memoir called The Seven Good Years, starting with his son’s birth and ending with his father’s death. I interviewed him about it at the 2016 Perth Writers’ Festival. By this time, I also had a son; my father had fallen off a roof and into a coma only two years prior to the event.

What was he like, face-to-face? He was funnier than you might think, more like his This American Life persona than the tender, vulnerable man who had occasionally surfaced in Keret’s short-form, philosophical wonderland of years and collections past.

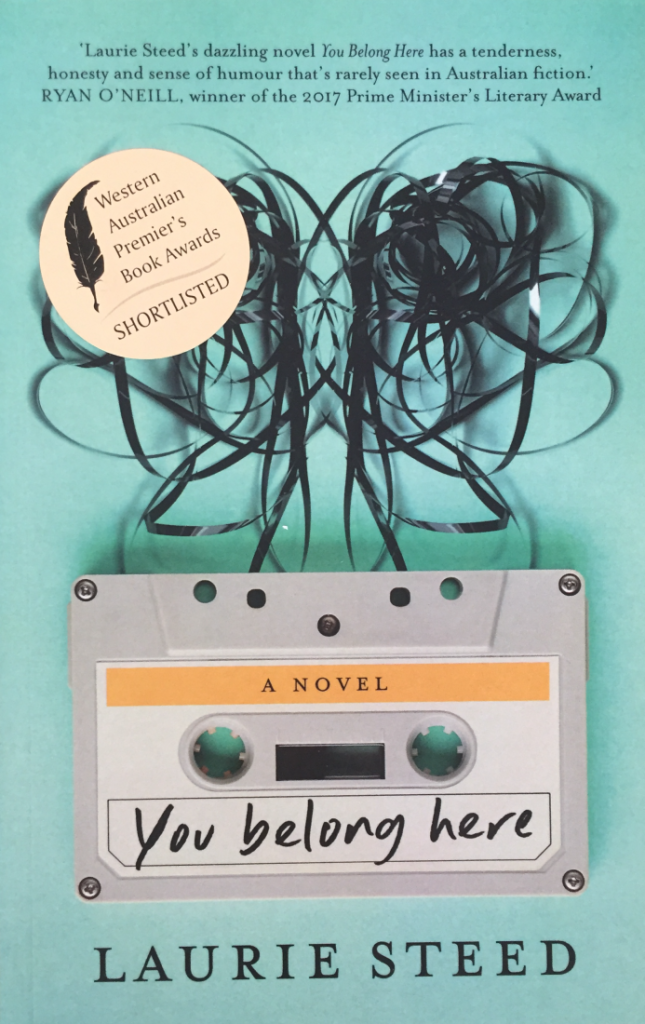

I asked Etgar if he would blurb my debut novel, You Belong Here, and he said yes. Only, as time passed, he ended up having to decline. He’d taken on a television writing project with his wife, the workload was snowballing, and something had to give.

While that was initially a bitter pill to swallow, in time, I found only gratitude when considering his words, thoughts, and legacy upon my life. Revisiting his memoir, I again found someone much like me. There were notable differences, Of course, in that he’d lived in a warzone, and I’d lived in a medium-density suburban development on the outskirts of Perth. In terms of where we were in our life cycles – the births and the deaths around us, ours seemed a shared reality. No longer were we two young men devoid of responsibility but more weathered men with families to care for alongside our writing.

Like Etgar, I was (or was soon to be) an author. Instead of being a distant inspiration, he was now a human being, similarly sifting through thoughts and memories in search of emotional truths. To his credit, perhaps he’d wanted to acknowledge that and be a colleague as opposed to a lifeline.

Keret’s life lesson— to never get too obsessed with another writer’s work or worth when it’s yours you should most focus on — was more profound than any I’d found while reading his stories. And indeed, he likely puts it best when he writes about a writer, in his story, ‘Suddenly, A Knock on the Door’ from the collection of the same name: ‘He misses the feeling of creating something out of something. That’s right — something out of something. Because something out of nothing is when you make something up out of thin air, in which case it has no value. Anybody can do that. But something out of something means it was really there the whole time, inside you, and you discover it as part of something new, that’s never happened before.’

Laurie Steed is a Western Australian author. His fiction has been broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and published in various anthologies, including Best Australian Stories and Award-Winning Australian Writing. His debut novel, You Belong Here, was published in 2018 and shortlisted for the 2018 Western Australian Premier’s Book Awards. His second book, Better Than Me: A Memoir of Early Fatherhood, will be published in September 2023 by Fremantle Press, and his third book, Greater City Shadows, won the 2021 Henry Handel Richardson Flagship Fellowship for Short Story Writing from Varuna – The National Writers’ House.

I can so relate to your last comment ‘make something out of something’. It is that second ‘something’ that is the catalyst for our poem or story, the raw plaster out of which we fashion a new and original shape.

Thanks for your comment, Dina! While it’s Keret’s comment rather than mine, it’s a great comment. So often, as writers, we forget to credit that part that comes from us and from thoughts, feelings, imaginings and memories, rediscovered. There are so many possibilities in that space, and yet somehow we often find our best fit for a particular piece. It’s alchemy, finding order in mental chaos; revisiting what was, and rediscovering it anew.