‘ . . . books, if they need to be written, will always find their moment.’

Geoff Dyer, Out of Sheer Rage

As writers, we often experience the thrill of discovering a new narrative strategy and applying it to our own creative endeavours. But sometimes a literary influence can be retrospective, like the value of a backdated cheque. Another way to put it would be to say that you can stumble upon a book that consciously articulates what you’ve unconsciously tried to express many years before.

So it was when I first read the ground-breaking work of creative non-fiction, Out of Sheer Rage, by English author Geoff Dyer. Published in 1997, the book would not come within my orbit until 2020, during Sydney’s second lockdown. The narrative ostensibly begins as an account of Dyer’s attempts to research and write a biography of D.H. Lawrence, which roams into a journal of false starts and procrastination. The diversions and tangents of involved in the research flow stubbornly away from the main story—rolling over the rocky terrain of self-loathing and angst before reconnecting with the central current. What Dyer has in common with Lawrence is what all writers collectively suffer, though at different times in their careers: the deadening realisation that your ambition for the book you’re currently writing does not equal your meagre talent.

A first reading of Out of Sheer Rage feels like a wild road trip through Lawrence’s life and work, with a stoned and ranting Dyer at the wheel of the tourist bus, lurching between lanes and around hairpin turns, as he points out landmarks associated with the famous author. But a second reading reveals a breathtaking structure as precise and well-rendered as a master cartographer’s map. Dyer’s efforts to understand Lawrence begin with collecting, and even stealing, photographs of his subject. A trip to an island to work uninterrupted on the biography results in the interruption of a near-fatal motorcycle accident. He makes a pilgrimage to Sicily, to the home in which Lawrence lived for three years. But when Dyer encounters an elderly woman who as a girl used to deliver the post to the famous author, he forgets, or even neglects, to ask her a single question. A train journey to the birthplace of Lawrence is hindered by multiple interruptions by fellow travellers, a journey that develops into a central metaphor for his process of writing the biography: ‘In a way I wished we were still in transit, were heading for some distant, hindrance-ridden destination so that we could all remain together. I was sorry to leave them.’

Dyer’s meditation on doing jigsaws also works on a figurative level and illuminates his process of writing the biography: ‘There was no plan to frame this book, to hold it in shape. I started in the middle with one or two images and am working my way outwards, to an edge that is still to be made.’

When he writes, ‘ the gap between resignation and active creation [becomes] almost insignificant,’ he is revealing his own struggles as a writer as much as his hero’s. Unlike most other literary biographers, Dyer doesn’t explain his methodology in an introduction, he simply enacts it throughout each subsequent chapter.

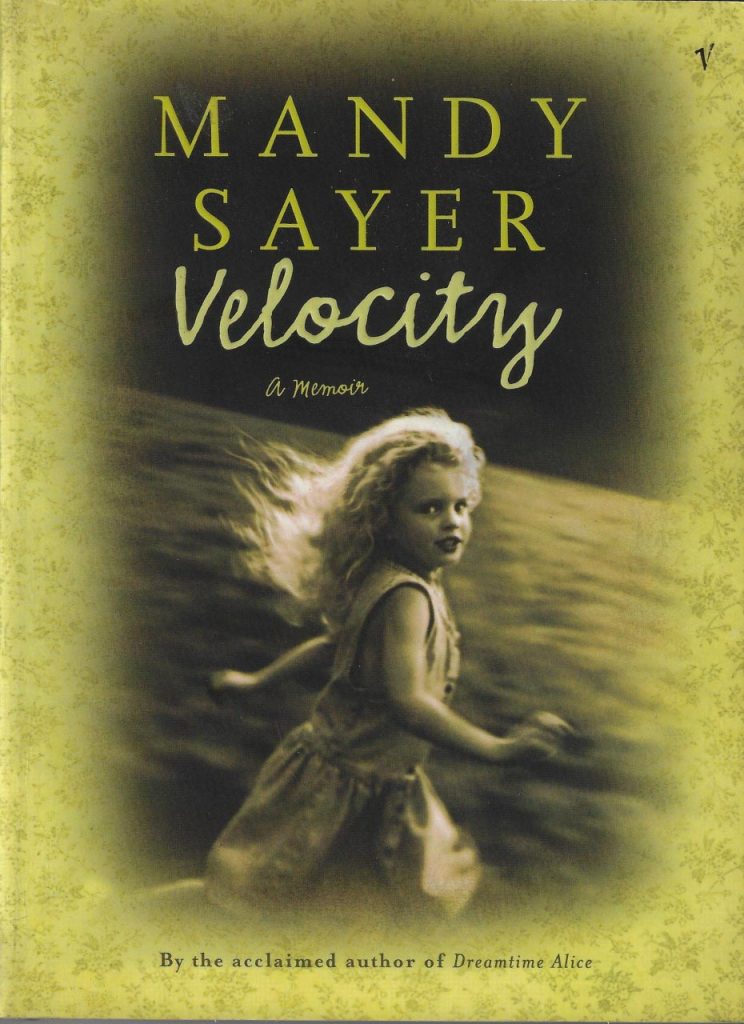

While certain books can influence a curious writer, so too can an author’s writing influence their reading. As I mentioned earlier, sometimes an influence can be retrospective, confirming in the present what you’d already determined, however unconsciously, in the past. While I could never claim to be able achieve the dizzying heights of Dyer’s narrative highwire act, for a long time I’ve been convinced that the structure of a book should clearly reflect its subject matter. This notion was first proposed to me as a teenager, not by a writer, but by a musician and composer who taught me, ‘concept before technique,’ or, even possibly, ‘concept is technique’. Another way to put this is that good writing doesn’t narrate experience but creates an experience for the reader. And while I’ve been conscious of this idea throughout most of my creative life, I believe the book of mine that achieves it best is my memoir of childhood, Velocity (2005).

Probably like Dyer, I stumbled upon the structure—and the experience I was trying to create for the reader–almost accidentally. The childhood I was writing about was chaotic, dangerous, and unpredictable, and I had a sense of wanting to unsettle and shock the reader as much as I had been as I was growing up—not just with the subject matter, but by how and when they learned of it.

While I’d decided to narrate my childhood chronologically in first-person, past tense, as I was mucking around at the computer one day, I heard a young girl’s voice speaking in present tense, narrating my experiences as they were currently unfolding. The girl’s voice was so vivid and compelling I eventually allowed her to lead me into a structure I’d never encountered before. While the individual chapters were standing on their own as solid accounts rendered in past tense, the present tense narrations began to elbow their way into the openings of the chapters, providing a preface, or even a premonition, of the experiences to follow. For example, a chapter that detailed the violence and sheer madness of my stepfather begins with an italicized present-tense passage that foreshadows the drama that will later unfold and be expounded upon fully in the past tense: ‘It is after midnight and my mother and I are in our pyjamas, rushing along the highway through the rain. The baby is in her arms, wrapped in a woollen blanket. My slippers are soaking wet and I can already feel a bruise swelling on my right cheek. Occasionally, a car slows down, tyres hissing against the wet road, but no one stops for us. ‘

However, when the past-tense narration appears again, it takes the reader back to twelve months before, just after the baby—my brother–has been conceived. The result of the present-tense foreshadowing is that the reader keeps being thrown into entirely new and traumatic experiences of the narrator’s future, without context or explanation. This structure aptly reflects chaos of my childhood, and in the process, one hopes, also disturbs the reader, which, just like Out of Sheer Rage, attempts to not only relate experience, but also create it.

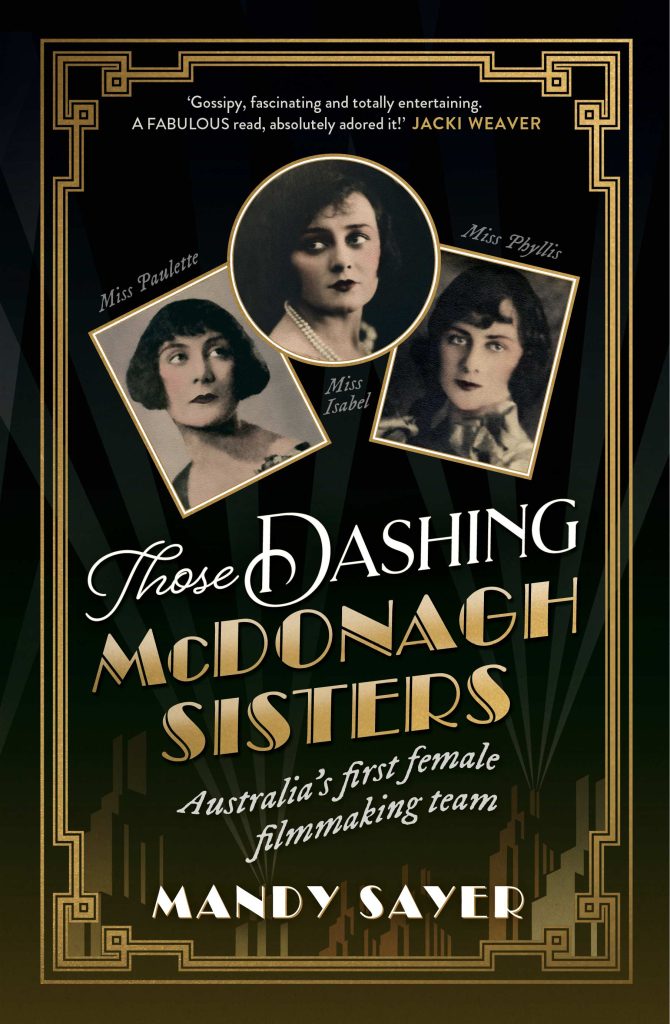

Mandy Sayer is an award-winning novelist and narrative non-fiction writer. Her most recent book, Those Dashing McDonagh Sisters: Australia’s First Female Filmmaking Team, has just been published by Newsouth Press.

Fascinating essay – I have loved Ten Thousand Aftershocks by Michelle Tom in part because her structure reflects a devastating childhood as well as the experience of living through a quake. Some fiction cleverly achieves this as well – Jackie Bailey’s recent auto fiction novel The Eulogy is structured as a eulogy which she has made overt with section headings from a eulogy handbook. I look forward to reading your memoir, Mandy.

Refreshing and helpful — thanks Mandy.