I began thinking about my fourth novel, Resistance – a novel about the craziness and steadfastness of family life – when I was undertaking a Masters in Family Therapy. Early in our training, we, the students, watched from behind a one-way mirror as our supervising therapist conducted a session with a (consenting) family. Later in the course each of us ran therapy sessions ourselves, with feedback from our supervisor via the phone on the therapy room wall.

My original title for this novel was Behind the One-Way Mirror, which says something about where I stood in regards to the subject matter: on the outside, looking in. I also toyed with the idea of setting the novel in the 1970s, when family therapy was a rapidly developing field of radical ideas. I commenced writing a realist third-person account of a young female therapist who was battling the patriarchy on various fronts and whose own family was a constant source of angst. A few months on it was clear to me that it wasn’t working. The plot was laboured and somewhat fraught. I wasn’t inside the writing. The whole thing was wooden.

Around this time I flew to Sydney for the weekend. As the plane taxied slowly to the runway, I opened Outline by Rachel Cusk and read the first few pages. Outline begins with Faye, the writer protagonist and first-person narrator, boarding a plane at Heathrow that will take her to Athens where she is to teach a writing course. For the next ten minutes my reading of Faye’s experience paralleled almost exactly what was happening around me in real time: the safety demonstration by the crew– always a strange ritual requiring a fair amount of cognitive dissonance on everyone’s part; the somewhat furtive appraisal of the passengers around me (are they going to be overly talkative or troublesome in other ways?); the busy comings and goings of baggage trolleys and maintenance vehicles on the tarmac.

The plane began to move, trundling forward so that the vista appeared to unfreeze into motion, flowing past the windows first slowly and then faster, until there was the feeling of effortful, half-hesitant lifting as it detached itself from the earth.

I read these words as the plane in which I sat detached itself from the earth and rose into the sky, exactly as Cusk described. (Take-off translates in French to le décollage; an ‘unsticking’, a more apt description of a plane defying gravity.)

But it wasn’t this episode of life imitating art that enamoured me of Outline. In fact, in the main, Cusk doesn’t aim for verisimilitude: Outline is an unashamedly non-realist work. Faye, the shadowy and largely silent narrator, is a keen observer of others, and it’s her observations that anchor and shape this minimally-plotted novel. While Faye maybe elusive, she isn’t without agency: she chooses what to report to us. We feel the shiver of her cool appraisal, the incisiveness of her judgment, without it ever being explicit on the page. The stories she’s told – or, at least, those she chooses to narrate – are largely about the relationships between women and men. Separation and divorce feature often. Families are fractured and children adrift. Instead of writing a novel about one unhappy family, Cusk creates a chorus of them.

It isn’t coincidental that this novel is set in Greece, home to Plato and his concepts of mimetic and diegetic narratives, and, of course, to Homer. Speaking in a 2018 interview for The New Yorker, Cusk says,

Partly, there’s the idea of this sort of communal storytelling, which is the whole basis of “Outline.” I was thinking about the Odyssey and about foundational narrative ideas and their relationship to therapy—people telling things after the thing has happened to them—and how that became a sort of basic therapeutic position that also evokes some commonality in experience.

People telling things after the thing has happened to them. I find this comment particularly interesting, not only because it relates to the confessional/analytical nature of therapy – the subject of my own novel – but because it points us also to the underpinnings of Outline’s narrative form.

What is this form? It is, as Cusk says, a communal narrative. Many stories are told to Faye by many different people: friends, acquaintances, fellow teachers and students. I’m resisting calling them ‘characters’; they don’t reappear throughout the narrative or show any capacity to grow and change. And, as is often noted by reviewers, they all speak in the same formal manner. Their shared voice is educated, articulate, reflective.

In the same The New Yorker interview Cusk says of the dialogue in Outline (and her two subsequent novels, Transit and Kudos),

‘Writing in inverted commas is what they’re doing.’

Here’s an example:

‘My first marriage,’ my neighbour replied, after a pause, ‘often seems to me to have ended for the silliest of reasons. When I was a boy I used to watch the hay-carts coming back from the fields, so overloaded it seemed a miracle they didn’t tip. They would jolt up and down and sway alarmingly from side to side, but amazingly they never went over. And then one day I saw it, the cart on its side, the hay spilled all over the place, people running around shouting. I asked what had happened and the man told me they had hit a bump in the road. I always remembered that,’ he said, ‘how inevitable it seemed and yet how silly. And it was the same with my first wife and me,’ he said. ‘We hit a bump in the road and over we went.’

As well as this non-realist dialogue, discursive and metaphorical, yet punctuated with conventional quote marks, Outline contains long passages of indirect or reported speech, narrated by Faye, such as this:

He began to see Dublin as he used to see it in his mind’s eye as a schoolboy, with scholars on bicycles sailing like dark swans through the streets in their black robes. Might what he had seen all those years before be himself? A dark swan, gliding through the protected city, free within its walls; not the American version of freedom, big and flat and borderless as a prairie.

Taken out of context this excerpt could be read as third person internal point of view but Cusk has chosen to cast it in indirect speech rather than consciousness alone. One could argue that this assignation is somewhat arbitrary, but when so much of Outline is cast as speech, both direct and indirect, I suspect that Cusk is asking us to pay attention to how words and ideas are conveyed as much as what is being conveyed.

During that weekend in Sydney, as I devoured Cusk’s remarkable novel, I realised that I’d found a form that fitted perfectly to the content of the book I was trying to write; a novel about a therapist and her clients, with wider themes of grief, abandonment and intergenerational trauma. My protagonist, a professional listener, could narrate her clients’ stories, and the thematic connections between stories would build to something whole. Like Cusk, I could make use of indirect speech to simultaneously relate events and interpret them, just as happens in the therapy room.

Here is an excerpt from Resistance, in which my protagonist narrator listens to a story from a woman she meets in a doctor’s waiting room:

Whereas her father leaned increasingly upon her, she said, nudging him with her shoulder as if to prove the point. Always the peacemaker of the family, he’d accepted his growing frailty with the same lack of complaint he’d shown all his life, so that if she told him tomorrow he was going into a nursing home, he wouldn’t put up the slightest resistance. And it was for that very reason that she was working so hard to keep him at home. Someone had to resist that final indignity, she said with emphasis, and if it wasn’t going to be her father, it had to be her. She’d taught high-school maths until recently and she saw the trajectories of childhood and old age as the application of centrifugal and centripetal forces respectively. As a parent, you stand in the centre as your children orbit around you, she said, and you exert a constant and steady force to draw them back to you, to stop them from spinning off into space. But your force weakens over time and their orbit around you grows more distant, and soon all you can hope for is an occasional sighting. By contrast, in the case of her father she was spending a lot of time and energy to keep him upright, so to speak, and to maintain a distance between them, minimal as it was, so that he still perceived himself as a separate, autonomous being. ‘That’s my gift to him,’ she said.

Articles cited:

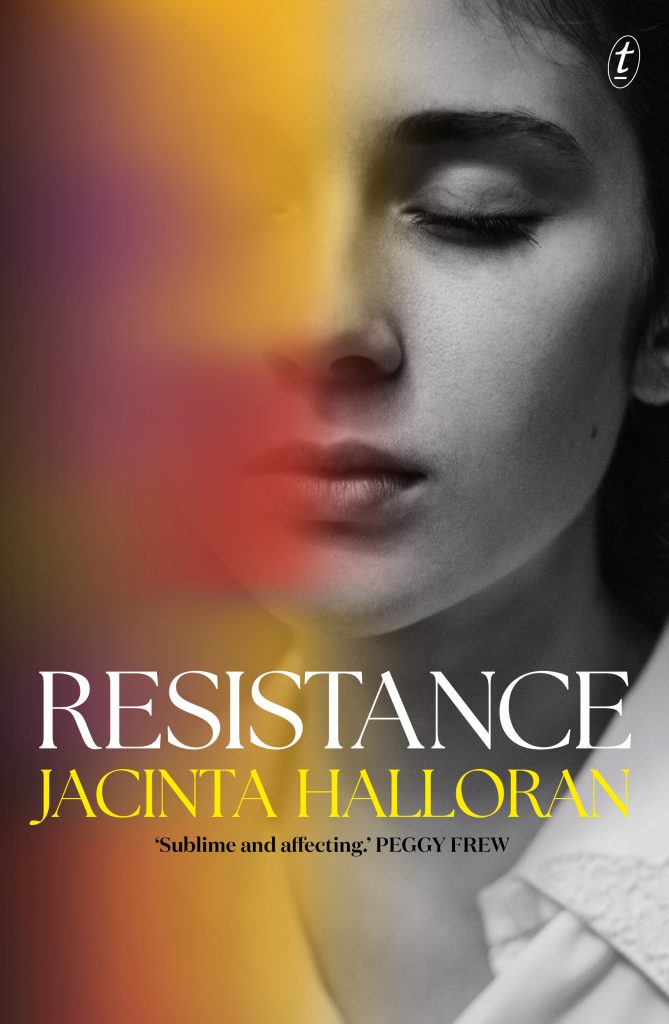

Jacinta Halloran is a writer, GP and family therapist. She has written for The Age and Inside Story and has had four novels published, the latest being Resistance (Text Publishing, 2023.) She is a former Board member of The Stella Prize.

Leave a Reply