Here’s your brief: write one sentence, or one phrase—one word, even—that will define your work, and you. It will be read more widely than any other sentence you’ve written, will be front and centre on your résumé, and feature in any publicity, introduction or accolade. And if you don’t do it well enough, as judged by your publisher, they’ll write it for you.

We’re talking titles, of course. Philip K Dick wrote no sentence more famous than Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (voted on Goodreads as the all-time title winner). Millions who’ve never read To Kill A Mockingbird are familiar with its title. My cv is, essentially, ‘wrote The Rosie Project’—which started as The Face of God, before passing through Natural Selection and The Klara Project.

When I was writing my first book, thirty years ago, my day job was in business consultancy. I asked one of our clients, the late John Iremonger at Allen and Unwin, how important titles were. Very, very important, he said, so I put some more thought into mine. Creative Data Modeling became Data Modeling Essentials. I suspect if I’d gone with the original, my book would have been seen as an idiosyncratic commentary rather than a central reference which is still in print.

Titles have high leverage: a big impact for just a few words and—perhaps—a single moment of inspiration. But unlike other high-leverage aspects of a book, such as the premise, the title remains in play right up to the moment the manuscript goes to the printer. Only one of my working titles made it through from conception to publication: Don Tillman’s Standardized Meal System. The Best of Adam Sharp began as The Candle; Two Steps Forward as Walk to the Stars.

So, as my partner, Anne Buist, and I planned our third collaborative novel, an episodic story set in an acute mental-health facility, its title turned out to be one of our biggest challenges.

There isn’t much research or advice around about titles. What there is, is largely about making them easy to find – in summary, unusual words help. If the searcher can remember them.

The Goodreads list of ‘best titles’ is interesting, but votes have likely been influenced by the contents of the books. Those big quirky titles—The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius—are in there, but so is Rebecca.

Kate Cuthbert of Pantera Publishing is completing a PhD on titles. She notes that certain formulas are going to be associated with particular periods. Girls, be theygone, on the train or dragon-tattooed scream ‘early 2000s’. (The original Swedish title of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is actually Men Who Hate Women.)

I don’t have a PhD in book titles. But I did study creativity and learned to set aside time for it rather than waiting for the magic. That means forty minutes every morning, shared with a walk, a light workout, occasionally driving. Plus, in the evenings, a session with Anne over the first glass of wine. (Two or more heads—another basic creativity technique).

So, here’s a short history of the creativity techniques we threw at our title, the options they produced, and the obstacles that scuppered all but one of them.

As soon as Anne and I began talking about the mental-health story, the title went on the agenda for our creativity sessions, intensely at first, then more sporadically. Good ideas take time—an incubation period. Best to start early, in our case, mid 2020.

Our first attempt came from playing with descriptive words: Illness, disruption, trouble—of the mind, brain, psyche…My brain’s search engine delivered a song. Song titles aren’t copyright and have a history of being appropriated as book titles: Norwegian Wood, Go Tell it on the Mountain, Rain Dogs. Our first pitch (for TV) was titled Trouble in Mind.

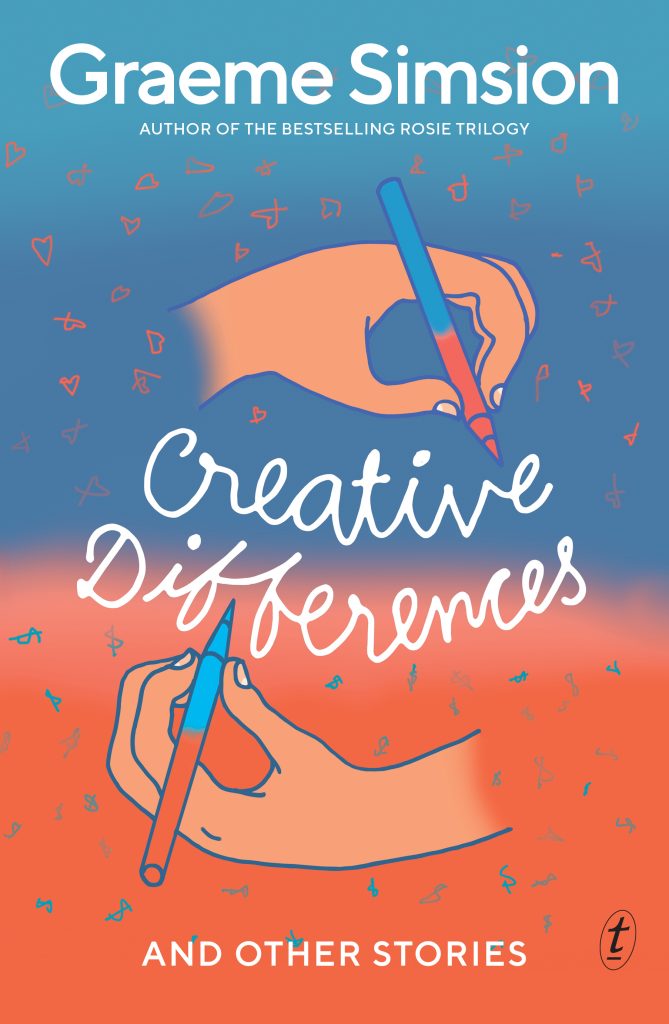

Unfortunately, it was also a movie title and a current Broadway musical. Too much, we decided. (Always check. Who’d have guessed Creative Differences and Other Stories had been used before?)

But songs…mashing two concepts together is a standard creativity technique. Mind Games? Not really what the book’s about, though a phrase from that song—Out of the Now—resonated. Song lyrics are very copyright, but John Lennon borrowed those words from a book. Album names are also up for grabs, including the most famous example with mental-health themes: The Dark Side of the Moon. DSM also stands for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the reference on psychiatric disorders. Neat.

The Dark Side of the Moon became the title of our first draft. By the time we submitted a proposal and sample chapter, we’d shifted to a line from one of the album’s songs: Remembering games and daisy chains and laughs. It didn’t connect in any way to the story, until we added one of the patients making daisy chains for therapy. Isn’t that, to use the vernacular, arse-about? No, it’s an example of how creativity works. But we couldn’t steal the lyric, and ‘laughs’ wasn’t the message we wanted to send about mental health, so our first submission was titled Daisy Chains and Stars.

Our publisher liked it, except for the last two words. So, Daisy Chains. Meant we didn’t have to add stars to the story. By the time the manuscript went to our beta readers we had three more options: Episodes, Brief Admissions, and Breaking Down, the last inspired by a blues song.

We kicked around a few dozen other titles, including variations on Thirteen Crises, Cries for Help, Minds in the Balance, Times of Trouble. And Acute. Simple, neat but we’d expect sequels, in other psychiatric specialities, to follow the pattern. Child and Adolescent? Not really.

Our beta readers voted for Brief Admissions, but our publisher liked Breaking Down. So did our TV agent. High fives. For quite a while, that was it. Until my UK publisher saw it: ‘I’m not going to publish a book called Breaking Down. Too much of a downer.’

English language editions usually have the same name. (Foreign language publishers may depart from a literal translation. The French title of The Rosie Project translates as The Lobster Theorem, the Italian as Love is a Marvellous Fault).

Our working title for the book series was Blue Sky Mental Health and our manuscript went to the international publishers as Blue Sky Book 1. Meanwhile, more brainstorming, now with the constraint ‘not a downer’.

We looked for phrases in the text. The glass-walled nurses’ station in the acute ward was called the fish tank. Lots of resonances there (which only matter if the readers see them.) It was the title for a few hours until Anne saw it. We kept generating ideas, some of them great to us, awful to others; some of them awful to everyone. Kissing a lot of frogs.

Then, out of the blue, as happens with problems you’ve worked at for a long time, came the answer. Out of the Blue. Acute crises happen out of the blue. We help patients out of being blue. In the Blue Sky series. Used elsewhere, but nowhere that’d compete or clash. Big thumbs up from our publisher. Eureka! Up it went on our websites and social-media profiles. We slipped the phrase into the text.

Beta readers were overall positive. Kate Cuthbert of the PhD on titles not so much (‘sounds like romance’), but you can’t please everybody.

Unfortunately, one of the people we couldn’t please was our new publisher and editor (the move is another story). They suggested…The Fish Tank. Been there, but we asked our beta readers. Yes! And No! The no’s came from clinicians and patients who found it offensive. Canned. But could we describe the workplace without the sense of voyeurism? We suggested Walls of Glass / Glass Walls. And back came our publisher with ‘House of Glass’ and then, four days later, full of allusions that we hope the bookshop browser and the reader will see, and supported by out beta readers ahead of everything that went before…

The Glass House will be published by Hachette in March, 2024.

The book with the ‘greatest title of all time’—Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep—was made into a classic movie. With a different title.

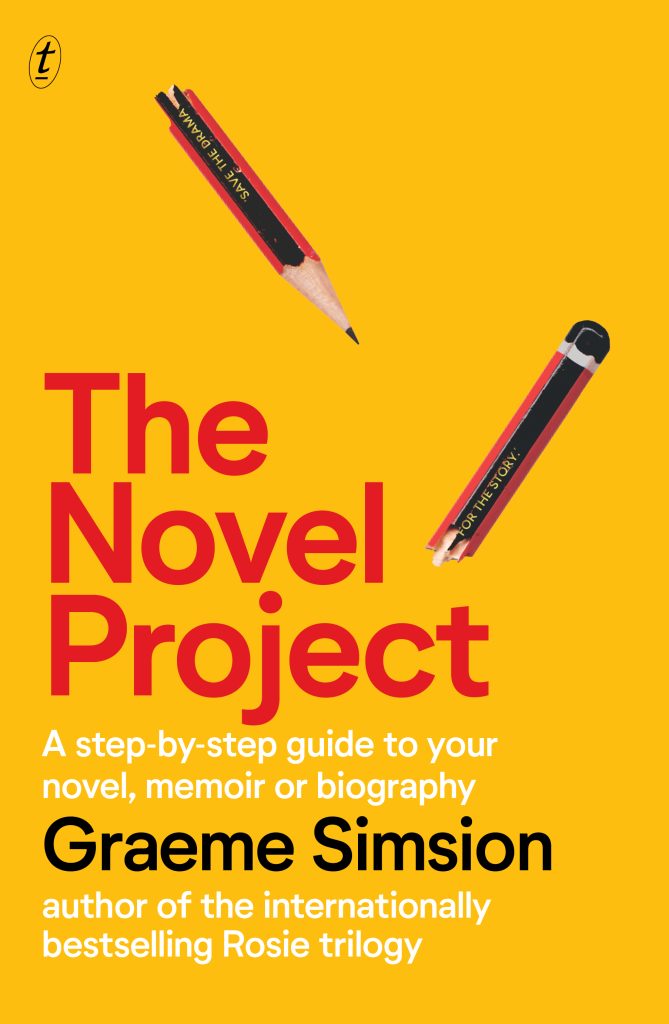

Graeme Simsion is the author of the Rosie Project series, which has sold over six million copies in forty-two languages, and other international bestsellers including The Best of Adam Sharp and the Two Steps series, which he wrote with his partner, Anne Buist. He is a regular presenter of seminars on writing, using his how-to guide, The Novel Project.

Thanks for sharing the inside scoop on titles! It’s fascinating to get a glimpse into the thought processes, and the different creative and commercial considerations, that go into choosing a title.

Magdalena, I’m glad you found Graeme’s article useful! x

Very generous of Graeme to share the process with us. Interesting.

Margaret, glad you enjoyed it and I agree – Graeme is very generous.

Greetings from Paris where I am about to start a 2 week CNF workshop with Patti Miller. As I munched on my freshly baked croissant for the morning (yum), I read with interest Graeme’s tips and tacking back and forth, as he works on locking down his book titles. I’m going to pay more attention to those titles on my 1200 Spotify playlist for starters. I remember sitting with a bunch of beta reader friends and asking for their comments on two titles I had come up with for the memoir I have been working on. The group were unanimous in their support for one of the two titles I have now adopted. Cheers.

Dear Richard, thank you for sharing your thoughts! So what did you end up calling your memoir?? Have a wonderful time in Paris; Patti is an incredible teacher 🙂

“Educating Riccardo” – who knows what any future publisher might make of it, but it works for me

I like it!