The recently departed Spanish novelist Javier Marías, asked once to identify the moment when he knew his vocation was that of writer, responded that in fact he had never wanted to be ‘a writer’. He drew a fine distinction between those who love the act of writing – self-sufficient, creative, private, often quietly beautiful – and those who actively want to be writers. Marías identified closely with the former, as do I; he also reinforced the conventional view that a love for the act of writing always has its origin in a love of reading. Merely to write is what counts: the complex and yet often ephemeral paraphernalia that goes with being ‘a writer’ was of no interest to Marías. To do, we might say, is more important than to be.

Lee has kindly asked me to discuss a book that has had an influence on my writing practice. I must make two confessions: firstly, I am a writer who rarely, if ever, reflects upon my writing practice. Of course, I think deeply about the content as I research and write, but I have no idea how or why I write the way I do. I can only say, selfishly, that I aim to write sentences and explore topics I would enjoy reading myself; like Marías, the act of writing, the intellectual and emotional craft, is more important than the resulting commodity, along with the social networks and required performances that emerge from publication. I have never tried to cultivate a ‘style’, nor write for any particular effect, and by extension have never had any aesthetic, and much less political, objective as a writer. In a contemporary environment where our national cultural policy is being discussed, the notion is often asserted that writers make a special contribution to society. My second confession is that, other than in limited and exceptional circumstances, I am highly sceptical of such claims.

How is influence measured? I’m not sure I can answer that question, nor am I sure writers are always aware of their influences. It seems an incredibly difficult matter about which to be objective. Is it not vanity and presumption to cite a famous writer as an influence? Writers we love and admire are teachers, first and foremost, at whose feet we learn; teaching is an act of kindness, learning an act of humility. It would be an impossible task to suggest any one book that has had the greatest influence on my writing practice. Thus, rather than focus on influence, with all the shades of nuance the word suggests, let me talk briefly about a work that I admire enormously, both for the epic content and for the character of its author: John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

To begin, the book as an object. I treasure my copy of Paradise Lost for the edition itself: an 1863 leather-bound volume with gold-trimmed pages, my late father bought it for me in a second-hand bookshop in Hay-on-Wye many years ago. It is illustrated with a series of black-and-white engravings that combine romanticism with extravagant Victorian religiosity. Each engraving is protected by fine tissue paper, making handling the book a delicate affair; this only adds to the sense of the near-sacred which is already encouraged, naturally enough, by the content.

I have always loved Milton’s poem – narrating the fall of the rebel angels from Heaven, Satan’s subsequent revenge on God by luring Adam and Eve into tasting the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, and their subsequent expulsion from Paradise – because it contains and reflects upon so much that has been central to the development of western thought and culture. Quite apart from its other many qualities, for the contribution it makes to the western canon alone Paradise Lost is an important and hugely valued work.

Like Shakespeare two or three generations before him, Milton was unafraid to coin new words, and like the Bard, produced work that is deeply wise and endlessly quotable. Many of his phrases have entered and enriched our language. Perhaps the most famous from Paradise Lost are ‘his dark materials’ – many will associate the term with Philip Pullman – and ‘red right hand’; here, many will immediately think of Nick Cave, one of countless artists who over the years have drawn on Milton. In only the first book of the poem, other memorable phrases abound: ‘darkness visible’, ‘the burning lake’, ‘the vast and boundless deep’ or ‘yon dreary plain, forlorn and wild’. These are all descriptions of Hell (‘this ill mansion’) where Satan and his colleagues find themselves prostrate, having been cast out from Heaven. In a series of overwhelmingly rich and exciting passages, the devils’ collective (Pandemonium) vow revenge and craft their plans for the overthrow of Heaven, until landing on the cleverest plan of all: to destroy God’s work by seducing his most treasured creations, Adam and Eve.

Here ensues another re-enactment of the fundamental clash between darkness and light, order and disorder, vice and virtue, obedience and punishment, independence and servitude, passion and reason. Milton is too clever to treat these as simple binaries; part of his genius – and Dostoyevsky would do the same two centuries later – was the way he gave the brilliant lines to the worst characters. William Blake famously commented that Satan was the hero of Milton’s poem, and that Milton was of the Devil’s party. Undoubtedly, in Paradise Lost, the Devil has the best tunes. The epic and highly articulate Satan is the revolutionary in Hell who rails against the forces of oppression, as Jesus Christ had been in Judea, as Milton himself was in mid-seventeenth century England. ‘Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven,’ he writes, a sentiment which later gave rise to Emiliano Zapata’s maxim that it is better to die on your feet than live on your knees. And how forward-looking was Milton, too, when he anticipated by a few centuries a basic tenet of modern psychology: ‘The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.’

Beyond the brilliant inventiveness of his language, I have always admired Milton his grumpy independence, his refusal to belong to majority or conventional opinions. Milton was a revolutionary in his own time, a Republican at a time of the overthrow of the English monarchy, an unrepentant advocate of free speech and freedom of the press at a time when such positions were truly dangerous. By the time he came to compose Paradise Lost he was old, blind and poor, and dictated the poem to his amanuensis daughter, a fact that makes the work even more astonishing. One need not share Milton’s stern religiosity to revel in the glorious language of the poem. Like those of his age, Milton was also a classical scholar, and Paradise Lost is a lesson in classical mythology, as well as providing insights into the cosmology and science of the day, much as Dante had provided a glimpse into the medieval order of things in the Divine Comedy. This brief passage will suffice:

As when far off at sea a fleet descried

Hangs in the clouds, by equinoctial winds

Close sailing from Bengala, or the isles

Of Ternate and Tidore, whence merchants bring

Their spicy drugs: they on the trading flood

Through the wide Ethiopian to the Cape

Ply stemming nightly toward the pole.

(Book II)

To conclude by returning to the question of the writer’s practice: rather than be so bold or vain as to suggest Milton has influenced me, I would prefer to say he has provided many hours of delight and taught me about two of the things I most seek and value in life: beauty and humility. This is what we take from great writers: solace, learning, the joy of shared experience. When I complete my current work in progress – a social, cultural and political history of Madrid I hope to be finished drafting within a year – I am unsure if I will write again. Writing is a joy, but it is not a vocation. There is already too much to read or, even more importantly in terms of the richness of the experience, to re-read. With the long horizon casting up into view, time must be put aside to spend with those old friends who have given me so much companionship and joy.

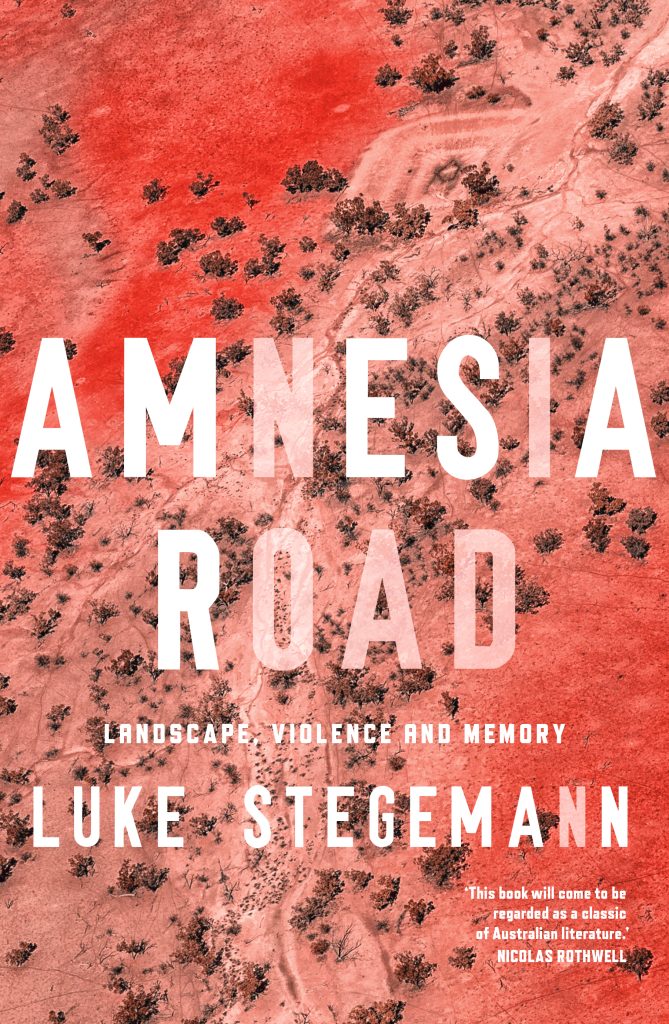

Luke Stegemann is a writer and cultural historian based in southeast Queensland. He has spent many years of his adult life living in Spain, and has written on art, politics and history for a wide range of Australian and Spanish publications. He is the author of The Beautiful Obscure (2017) and Amnesia Road (2021), winner of the 2021 Queensland Literary Award for Non-Fiction, the Mark & Evette Moran Nib Literary Award and runner-up in the NSW Premier’s Prize for Australian History. He is currently writing a social, cultural and political biography of Madrid.

I really appreciated this post, Luke. Deeply considered, nuanced and honest. And although by your admission of uncertainty in the final paragraph I am tempted to say, Please do keep writing, I find that I hold only respect for what is clearly a total and unreserved surrender to the process. Best wishes for your work in progress, and thank you for such a thoughtful read.

Thank you, Kim. That’s very kind of you. My very best wishes.

I loved this thoughtful post Luke, identifying with you as someone who loves the act of writing rather than the outcome. I’ve never read Paradise Lost but am intrigued, having been fascinated by Dante’s Comedy. Valuing beauty and humility in life – and in writing – yes indeed. Thank you.