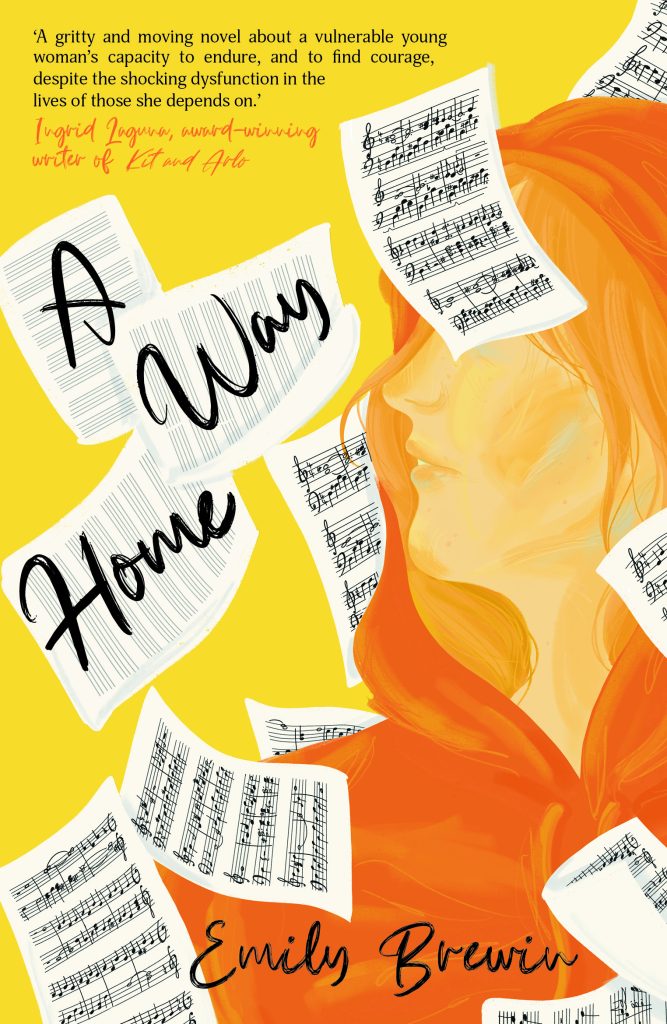

My most recent novel and my first Young Adult one, A Way Home, is about a sixteen-year-old girl who finds herself homeless in Melbourne’s CBD during a particularly bitter winter. Since we met her, Grace has been living rough for almost three months, camped on a hidden ledge under a bridge. She’s scared and isolated but determined to keep to herself until she can figure out how to find her way home —back to a place of safety and belonging.

Throughout the novel, I work to bring the reader into Grace’s world, where things we take for granted, like showering, staying warm, finding food, and creating meaningful connections are not always available.

But as someone who has never experienced homelessness, I could only guess what living rough might be like. To ensure Grace was well-rounded, and to present an authentic and informed account of life on the street, I needed to speak with people who’d had this experience.

Simply interviewing such people wouldn’t make me an expert, but it would provide insights I couldn’t get any other way. But, where would I find these personal stories and what ethical concerns would I need to consider while gathering them?

For instance, I didn’t want to simply approach a homeless young woman on the street and request an interview — especially if she was a minor. Whoever I interviewed needed to be properly informed and renumerated for the time and stories they offered me.

I found the Council for Homeless Persons website and their Peer Education Support Program (PESP). The PESP ‘supports people who have been without a home to advocate and speak knowledgeably about the systemic and structural issues behind homelessness.’ Through the program, I met a woman who had experienced homelessness as a teenager and was willing to speak with me about what this was like.

From here, I contacted other agencies for interviewees. Going through these organisations alleviated my concerns about inadvertently taking advantage of people. Melbourne City Mission pointed me to their specialist youth service, Frontyard, which works with young people who are at risk of or experiencing homelessness. I spoke to Frontyard staff about the nature of youth homelessness, which gave me a sense of the daily and systematic challenges Grace might encounter. I also engaged a staff member to conduct a sensitivity read of my manuscript.

Additionally, I spoke with young people who’d grown up with a parent with a serious mental illness, as Grace had. I reached out to The Satellite Foundation which ‘connects and empowers children and young people who have a family member living with mental health challenges’. The Foundation sourced two interviewees, Laura and Nathaniel, who were in their twenties and had grown up with mothers living with mental health challenges similar to Grace’s mother’s.

I met separately with Laura and Nathaniel at cafes. Both were generous and candid with sharing their personal stories, speaking of how parental illness shaped their lives into adulthood. Specifically, growing up they were often hypervigilant of their mothers’ emotional state — to the point of feeling enmeshed with and responsible for it. Their insights informed the way Grace interacts with her mum, Liesel, whose mental illness periodically impacts her ability to care for Grace. And Grace often feels helpless in the face of it:

Mum’s illness is like an ocean, sometimes calm, sometimes stormy, but always so immense it’s hard to see the shore. Just when I think life’s improving, the wind picks up and the waves grow into mountains again that threaten to shipwreck us. The sickness is Mum’s, but it half drowns me too.

The personal stories I heard while writing A Way Home were usually raw, and difficult to hear. They were also rich, complex, and honest. I conducted interviews for my book throughout the redrafting of it. As I refined the story, it became apparent where the gaps in my knowledge were and where the story needed building up. For instance, in the final draft of the novel I included a scene where Grace is sexually assaulted in an alleyway one early evening.

Then a force, so great it knocks the wind from me, hurls me to the ground. Suddenly, the guy is on top of me. His body pressing down as I struggle for breath. I cough and wheeze, try to call out, but my voice has deserted me.

I knew young women experiencing homelessness often suffer this type of violence, but I’d shied away from writing about it, afraid I might not do it justice. To gain confidence and understanding to tackle such a scene, I interviewed professionals working in frontline homelessness services. Their stories informed Grace’s attack, and the physical and emotional aftermath.

Every now and then I’m asked what techniques I used to draw out the information I needed. My process was simple. Before the interview, I’d compile a list of questions, ask my interviewee if they’d like to see them in advance, explain my interview process, and seek permission to record our session. All this was done via email.

I wanted my interviews to feel relaxed, as informal as possible. At the beginning of each one, I’d tell the interviewee to answer my questions however they saw fit, including not answering if they didn’t want to. I kept most interviews to around 1-1.5 hours. I’d also veer from the questions if something piqued my interest or required more attention. In every instance, rapport, curiosity, and a willingness to listen were the most important tools I had.

In the end, many generous people contributed to the writing of A Way Home. I can’t understate the value of the energy and information that came from these interactions or the colour and detail I was able to inject into the novel because of them. If you’re also thinking of using interviews to inform your writing, I encourage you but suggest you think of the process as a two-way street. One that involves empathy, non-judgment, and trust.

Emily Brewin is a Melbourne author. Her first novel, Hello, Goodbye, was published in 2017 and her second, Small Blessings, in 2019. A Way Home (2024) is her first young adult novel. She uses storytelling to explore social issues in an accessible and engaging way. With a background in journalism, Emily uses research and lived experience interviews to inform her novels and her writing presentations.

Impressive process Emily. Well thought out and respectful. I can’t see how it wouldn’t bring depth and truthfulness to your novel.

Sandra, thank you for these kind words about Emily’s piece!

Such a wonderful, practical and insightful piece, thank you Emily (and Lee) – the vulnerability expressed in an interview is a two-way street as well, so thank you Emily for not only exploring crucial social issues through your fiction but braving up and doing the work with such care and consideration. It’s clear how this makes for nuanced and enriched storytelling. All best wishes for your book and writing! Bianca

Thank you for your thoughtful comment, dear Bianca!