I was boarding the plane in Paris on my way home from the annual memoir-writing workshop, when I had a sudden jolt of recognition. That magnificent head of swinging auburn hair several metres ahead could only belong to my ex-friend Gina who had unceremoniously dumped me the year before. How weird, how apt, to run into her in Paris where our friendship had blossomed! The cafes we had been to. The walks we had been on. What would I say to her when I passed her seat on the ‘plane? Ignore her? Nod? Stop and greet her politely?

Then the woman turned to check her wheeled bag, and of course it wasn’t Gina.

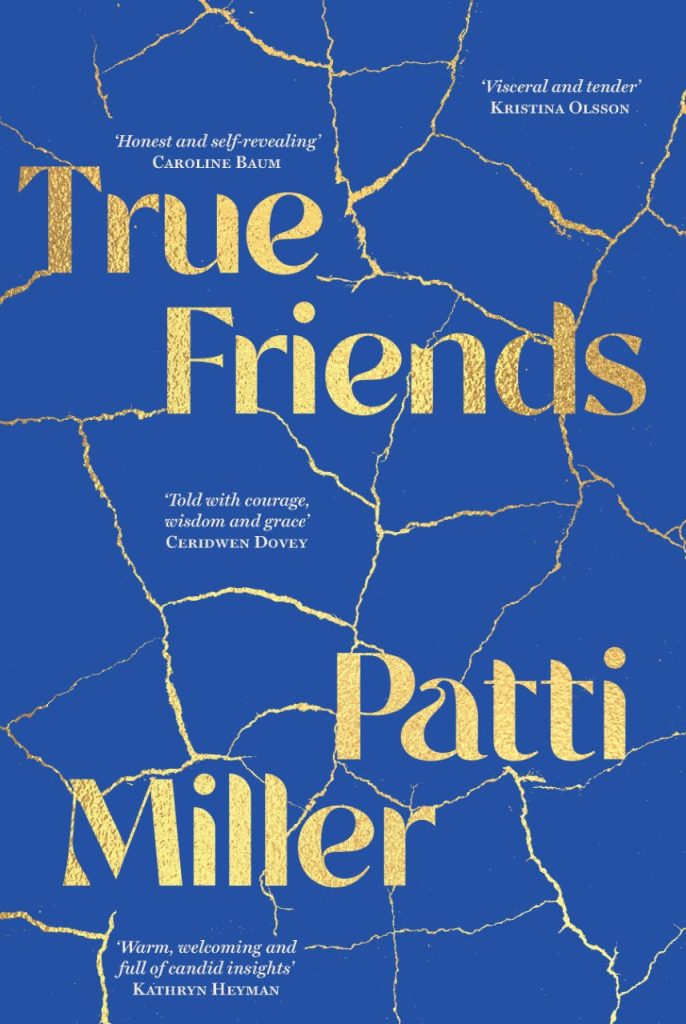

After I had stowed my bag and settled in with my books and notepad, I thought about how quickly my mind had built a full picture of my ex-friend from a swing of hair, how quickly memories of our joyful past had rushed together, and then how anxiously my body had responded. As is my way, I started taking notes about what had just happened, trying to analyse what my brain had so rapidly done. By the time I alighted in Singapore for a brightly lit stopover, I had a mess of questions about how memory and our awareness of others function in the brain – and the beginnings of my new book, True Friends.

Back in Sydney I sat down to start writing the story of my friendship with Gina and began to research the neuroscience of memory and perception. I already knew not to gather mountains of information first – I had seen too many writers stopped, sometimes forever, at the foot of the daunting mountain of research they had done. In fact, my number one rule for research is ‘research as you go’, i.e, write, then research as you find out what you need to know, then write some more, research some more, write some more.

As I wrote, I wondered why friendship, compared to romantic love, was so little written about and started investigating writers who had explored friendship. Of course I had to include the first written story, The Epic of Gilgamesh, about two friends and the end of their friendship through death.

Now I had the neuroscience of memory and The Epic of Gilgamesh to weave into my story! What on earth was I thinking? How could I possibly insert contemporary science and ancient literature into my memoir?

There’s basically only three ways to use research – direct extract, re-phrasing of original material, or a mixture of the two. When it comes to using science research, a direct extract can result in a shiny but out-of-place piece of technology in my otherwise ‘natural’ writing environment. I decided to use very small pieces of verbatim and then do my best to explain the science in my own words. This obviously means I needed to understand the science, so there had to be a great deal of re-reading and note-taking. But then, due to anxiety about getting facts embarrassingly wrong, the first draft sounded very like the original article. So I wrote it again, and again, each time understanding it better and therefore more able to put it in my own words.

And that’s my second piece of research advice: read and take notes to understand ® write what you understand® understand better ® rewrite.

It was easier in some ways when it came to The Epic. It was already literature after all, poetic, powerful, emotionally engaging. But I couldn’t be sure how many readers would be familiar with this ancient text, so I decided to briefly rephrase the story near the beginning of True Friends. There was a danger of The Epic overbalancing my story, so I needed to make sure the re-telling voice was consistent with the voice in my personal story. I was able to re-tell certain parts of the story in closer detail, connecting them through theme or image to the friendship stories I was telling from my own life. For example, in this extract from True Friends I make a connection between friendship in The Epic and in my own experience via the idea of ‘likeness’ as the basis of friendship.

“Enkidu was formed by the goddess creator, Aruru, who made him from ‘the stuff of Anu’, the firmament; she made him of water and clay to be the equal of Gilgamesh, to be ‘as like him as his own reflection, stormy heart for stormy heart.’ The ground of their friendship was their likeness, they shared a restless passion.

Common wisdom says we are attracted to those who are not like us, but perhaps the opposite is true in friendship. Perhaps the joyful feeling in friendship is seeing your inner self recognised and reflected.”

I also decided to use direct extracts of The Epic’s beautiful poetry. I wanted readers to have some sense of the kind of language – translated into English – that the ancient story-tellers had used. I simply used favourite bits, no highly organised reasoning here. Apart from the ‘research-as-you-go’ method, which cuts down massively on excessive and unnecessary material, I’ve developed over time a ‘sparkly bits’ approach. I read a lot but only take what ‘sparkles’, what catches my eye. I note where I have found it, jot down whatever I love about it and then decide how I am going to use it.

Part of my purpose in True Friends was to explore the need for telling stories about our lives. Memory is the first story-teller, the first creator of fiction some researchers say – our first impulse is to make a story about what has happened. Then comes the impulse to write it down. I re-read The Epic of Gilgamesh and was struck by the fact that the tale was also about the importance of story-telling itself. How extraordinary that the first story was also about why we tell stories.

The research on the neuroscience of memory and The Epic were integral to the story of a friendship and of story-telling itself, but most of True Friends is my story. The research is proportionally small.

And that is my last piece of advice about research – it needs to be deeply related to your purpose, not there for padding or to hold your story up or show how clever you are, but to be part of the heart of it. Come from the heart of your story to the research and soon there will be a flow between the two. For me it meant that True Friends was not just about me, it was about all of us, our desire for connection, our need to be part of the human tribe, and what happens when we feel caste out. Research connects us and our stories to a bigger world, making the personal also universal.

Patti Miller – author of ten books including best-selling writing texts Writing Your Life, The Memoir Book and Writing True Stories; a novel, Child; and six books of creative nonfiction, The Last One Who Remembers, Whatever The Gods Do, the award-winning The Mind of a Thief, Ransacking Paris, The Joy of High Places and her latest, True Friends. Her personal essays and articles are published regularly in national newspapers, magazines and literary and art journals. She teaches memoir and creative nonfiction around Australia and gives memoir courses in Paris and London each year. http://lifestories.com.au/

Thank you for this article. It is much appreciated. I am a retired psychologist writing a book about my relationship with my father, who suffered at the hands of a sadistic mother and a mute/absent father. I am writing it as a memoir, but, having done extensive research into my dutch family I have a number of stories that I want to weave into the narrative, as part of an intergenerational dimension to the book. I know some of these stories very well having spent significant time in Holland undertaking extensive research. Some I don’t know so well, but think that I can bring into the narrative by means of creatively written pieces that I will acknowledge as my imagined story. Eg., the story of the funeral of my father’s six-year-old brother during the war. I know this story well through my father’s recollections and an uncle’s diary. However, there are pieces that I need to fill in to create what I consider a well-rounded narrative. Is this acceptable?

Peter, to my sensibility it is acceptable to ‘re-create’ scenes because you are not writing verifiable history but a memoir/creative nonfiction. You are trying to create the texture of lived experience, rather than write a record. So long as the reader does not feel you are ‘taking them for a ride’, they will accept your re-creation. All best with your writing, Patti