As a young journalist and TV producer starting out in the misogynistic, rough and tumble world of commercial television in the 1980s, I quickly learnt that in order to survive, I had to hide any outward signs of vulnerability. Despite the many occasions I found myself in situations that were unacceptable – especially in today’s post #MeToo era – I grew up believing that revealing any signs of professional or personal vulnerability was a sign of weakness. It was necessary as a young female to just ‘suck it up’ and deal with any issues privately.

At the same time, I was learning that being a good journalist was all about spotting and objectively telling other people’s stories… never your own. At countless dinner parties and other social events, I would pepper those around me with a thousand questions, deliberately deflecting and never revealing anything of a personal nature.

Fast forward to 2013 and a family dinner in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. Sitting around a long oak table were mainly journalists and lawyers. The increasingly rowdy conversation turned to a triple murder case dominating the headlines. Then something triggered one of the lawyers to look me straight in the eye and ask:

Do you know about that infamous long-running court case? The one in the 1950s involving your father?

I was floored. I had no idea what he was talking about. At the same moment, I could feel every journalistic bone in my body tingle with intrigue. I was driven to find out more about this court case, changing hats from daughter to investigative journalist. I had spent more than thirty five years researching and telling stories about other people –often elusive stories with delicate details. I knew how to piece together lives from the other side of the world. Now, I felt compelled to dig in my own backyard.

It was to take almost three years of digging to uncover the 1953 court documents, long buried in a government records repository. Within these 600 pages I was confronted by the warts-and-all anatomy of a corrosive marriage, and a fascinating insight into the private lives of 1950s middle-class Australia. Here my father was fighting with one of his four wives years before I came on the scene, a woman I barely knew existed. The transcript of their case captured the disintegration of a marriage so clearly, and was so rich in detail, that I felt a spooky sense of being a voyeur in my father’s private life. Perhaps that’s because he kept this episode utterly hidden from me and the family. It was then that I knew I had to turn my father’s story into a memoir, to uncover a fascinating tale of a political refugee arriving in a fairly ignorant, mono-cultural country, particularly since some of those attitudes still exist today.

Writing my first book, especially a deeply personal memoir, is undoubtedly the most difficult project I’ve ever undertaken. In the beginning, I set out to research the ‘infamous long-running court case’, and write this for my family. But the more I dug into my father’s past, the more extraordinary the layers of his life I was discovering.

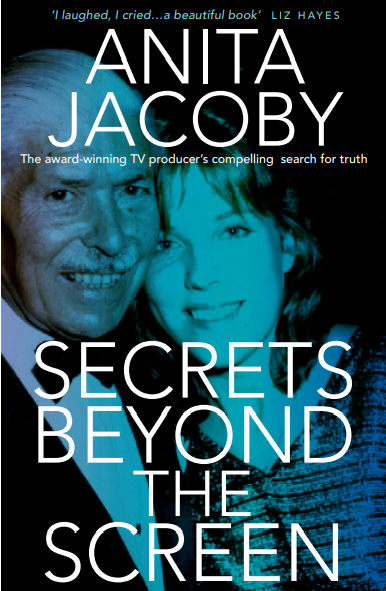

My father Phillip Jacoby was a German political refugee with Jewish antecedents, who fled Nazi Germany on the eve of World War II, arriving alone and penniless in Australia at the age of twenty-three. Like so many of those escaping persecution, my father only wanted to look forward, never back. He became a pioneer in Australia’s communications industry and was respected in the political, business and entertainment worlds. But as I was to discover, my father was an international man of mystery. His life was an extraordinary story of long-held secrets, forbidden passions and political intrigue; a story of spying at the height of the Cold War, a doomed love affair and one of the longest running court cases of its kind in Australian legal history. That was why what was originally going to be a short-term project became six years of research, through a maze of blind alleys and dead ends, and eventually towards the discovery of hundreds of pages of archival records, secret police files, court transcripts, historical hand written notes, newspaper articles and lengthy police interviews with my father, all of which had remained hidden from my family for more than six decades.

As the richness of my father’s story gradually revealed itself, I wrestled with exposing his life history and painful past, in the public domain. An inner battle between the protective, loving daughter versus the objective journalist, who recognised our family stories are often the most fascinating of all. I suspected there will be others who would relate to my unnerving discovery that despite our always close and loving relationship, I never really knew my father.

It took an enforced period at home during Covid to pivot 180 degrees, from a family history to writing a deeply personal memoir. Over time I came to realise that as a journalist, finding ‘my voice’ wasn’t as difficult as I first imagined. It was all about finding and revealing some of my personality. I needed to just be myself and ‘my voice’ would follow.

I came to also understand that exhibiting vulnerability on the page was not a weakness to be ashamed of … it was actually showing strength. I found I was able to write about my father’s traumas – including his long battle with Alzheimer’s and the impact on him of a motorbike accident I had – which had profound consequences on his health and our close relationship.

I never viewed the reason for writing a memoir as being cathartic. There are other more effective ways of coping and processing painful events. But through the act of writing I also came to understand myself much better, whilst strengthening relationships with others.

Memoirs are about facing our pasts. They’re about facing our families, together with sifting through and understanding our past experiences. I now recognise they allow us to make sense of the world.

Anita Jacoby AM is a leading advocate for women in media and leadership. As one of Australia’s most distinguished television producers, Anita rose to the top of the media as Managing Director of an international production company, ITV Studios. Prior to this, Anita managed Zapruder’s Other Films responsible for many successful programs including Enough Rope, Elders and Hungry Beast. Anita currently Chairs the ABC Advisory Council, co-chairs Women in Media, is a Member of the ACMA, and a Director of Chief Executive Women, the UK Board of the Duke of Edinburgh International Award and Documentary Australia. Secrets Beyond the Screen is her first book.

Anita, thank you for this post. It highlights for me the strength of allowing vulnerability and honesty into the writing space. Memoirs are hard work, I suspect. I have always avoided the urge to write one in order to protect my vulnerability and associated shame, however your words have me thinking!

Heather,

Thank you for your feedback. I totally agree that memoirs are really hard. I’ve also found myself telling plenty of people it’s not an autobiography … there are whole slabs of my life I deliberately left out! Perhaps you will come around to writing one a memoir and if you do, I wish you all the best with this project.

Anita, thank you for this candid article on memoirs and vulnerability. It’s helped me immensely at a time when I am getting ready to write my memoir: my story starts in a small town in India through several countries and now Australia. Belonging to a dysfunctional family. I have to be strong to let my vulnerabilities come through with the written words.

Any chance of having a chat please? Rubina Smith, Brisbane 🙏

Hi Rubina,

Thanks for your comments. Finding strength on the page is no easy task!

I’m happy to have a chat after Easter. Perhaps Lee can connect us via email.

Dear Anita, thank you for sharing your story with us. I look forward to reading your memoir. I wrote my own story, “A Dangerous Daughter, “ not as a memoir but as fiction. It helped to distance myself from a painful past while facing truths long since buried. I agree with you that the writing process itself is not cathartic but the revelations and truth are themselves healing.

Hi Dina,

I appreciate your comments. I can well understand when something is so painful, it’s somewhat less confronting to fictionalise large parts of your own story rather than write a memoir.

I’ve just gone online and read about your book. It sounds very compelling. Will definitely order a copy in.

True, but what matters more is celebrity status, social media platform and fitting the current “diversity” slot to guarantee sales. Those without that can be as vulnerable as they like but they will never be traditionally published unless they agree to a “co-investment” or “partnership publishing” where they pay $5000-$10,000 to share the risk. Be wary.

Jane, yes, the publishing industry is precarious right now and is particularly averse to risk. Having said this, from what I see around, genuinely well-written works (so also vulnerable) tend to find home eventually, even if with smaller publishers.