The desire to write about my mother’s Holocaust story had been with me for awhile. Like, thirty-five-years awhile. I had been a published writer from the age of 19, when on a whim I’d sent a humorous piece about my student holiday trip to The Age, and they published it as a full page article, together with an oversized photo of my face. Before long, writing became my main gig: freelancing, working as a staff writer at magazines, editing, starting websites. But I had never written a book.

The prospect of writing a book was paralysing. I had grown up with books all around me, literally: my brother Fred, nineteen years my senior, had co-founded Australia’s first independent publishing house, Outback Press, when I was seven, and would go on to publish Kate Jennings, Morris Lurie, Elizabeth Jolley, Carol Jerrems. When I was eleven, Fred handed me a manuscript whose title was confusing to me, and so it was promptly changed. Very early on, I could see how these typed sheets of paper could become something so much more substantial: a book read by thousands, that might appear in libraries and schools, that could become the thing you kept in your head and your heart.

The first time I considered writing a book was after I’d lived in the US for almost a decade, interviewing celebrities. It’s my party trick: name five movie stars of the 1990s, and I guarantee you that I’ve interviewed at least four of them. Julia Roberts? Yes, twice. Keanu Reeves? More than I can remember. But when a publisher approached me to put these stories into a book, and include my personal experiences in the mix, I retreated. I had been perusing the spines of my brother’s book collection ever since I could walk, and it was where I learned about so many authors: John Updike. Anthony Powell. Miguel de Cervantes. Philip Roth. I revered their names and their work. I would delicately lift these books from the shelves, fanning the pages to emit that old-book smell. As an adult, when I looked at the alphabetised books in my home and dared to imagine my work among the others, I saw that mine might sit between Anne Tyler and Gore Vidal, the only “U” name. But first, I would have to produce something that was worthy of the inclusion. A book about being set up on a blind date with Alec Baldwin wasn’t one of them.

In some corner of my mind and heart, I always knew the book I’d one day write would be the story of my mother Mira, a Holocaust survivor who had endured four concentration camps at the age of 17, whose names I knew like a haunted recitation: Plaszow, Auschwitz, Ravensbruck, Neustadt-Glewe. But what stopped me, again, came down to books: I had read the works of survivors Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel – the only fan letter I had ever sent an author was to Wiesel, who promptly responded – so what business did I have to add to that bibliotheca? My mother’s story was worthy, but I, as the proposed writer, could not compare to those greats. And so, again, I stalled.

My idea picked up speed during the pandemic, when suddenly shut down offices and shut in people led to everyone I knew, seemingly, writing a book. (A friend dropped off a story of his life to me, some 1000 pages…) One lockdown gave me the opportunity, but instead I learned how to make sourdough bread. The second came and went. By the time the fifth lockdown had ended, I still had done no writing – although I had thought about it constantly, obsessively. Occasionally, I got so far as to write a few pages, but reading them back they sounded stilted and awful. Years earlier, I had tried to write an outline of my mother’s story, but by the time I got to chapter 13 – about halfway through, I thought – I gave up. I didn’t know how to structure a book; I didn’t know how to give it momentum.

It was lockdown number six that proved to be the charm. I had started to feel the kind of anxiety that comes with inaction, and the kind of self-hatred that arrives after you’ve told several people about your intentions, but haven’t managed to follow through. One day I went for a walk with my neighbour Diana, whose personal difficulties prompted her to ask about my mother Mira – herself proof that one could encounter unfathomable loss and still live joyfully thereafter. At one point, I started complaining about my freelance journalism: about all the magazines that had closed down or gone into hibernation; about the commissions I was no longer getting. ‘But I do want to write about Mira,’ I added. Diana stopped me, immediately. ‘Isn’t that what your legacy should be?’ she asked. And there it was. Something about the word ‘legacy’ ricocheted off the pavement and into my ears. My legacy, yes. But also: Mira’s. There was the very real chance that her Holocaust testimony would eventually be one of the many that got filed away in a museum, gathering dust. Yet I knew her story had some significant lessons to share – not just about the Holocaust and hate and antisemitism, but also about faith and humanity and connection and finding one’s way out of the darkest shadows.

The next day, I sat down at my desk with a different intent. I was going to sit there and write, every day, from morning through evening, until I had a draft. I was going to forget about a plan. I was going to forget about the half-hearted attempts I’d made. I was just going to write and forget about all the noise, about Primo Levi and the fact that everyone said it was almost impossible to get a book published. I would just write.

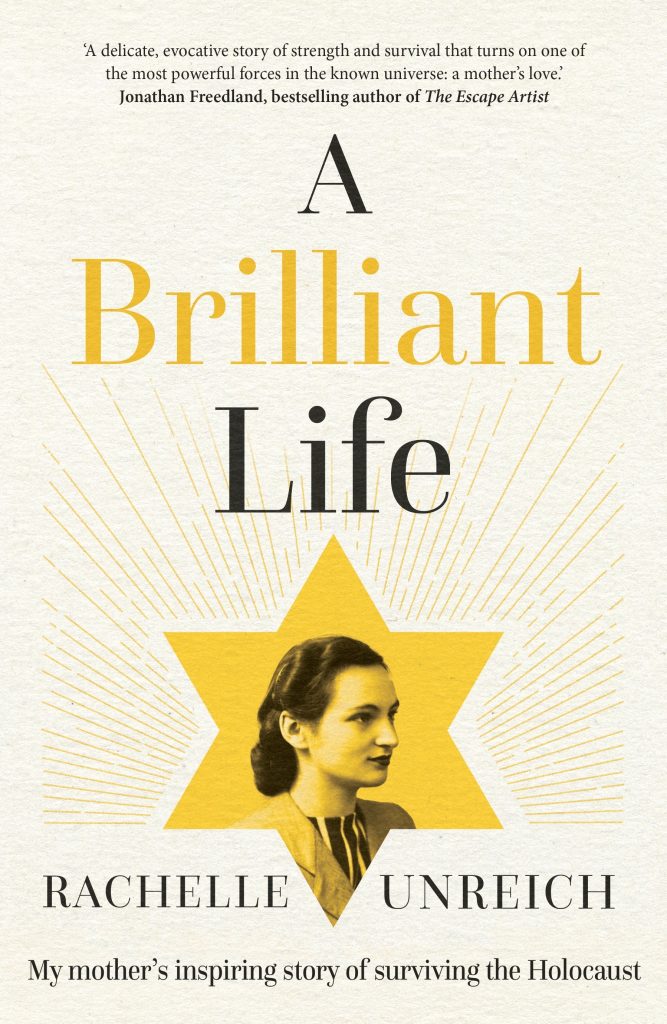

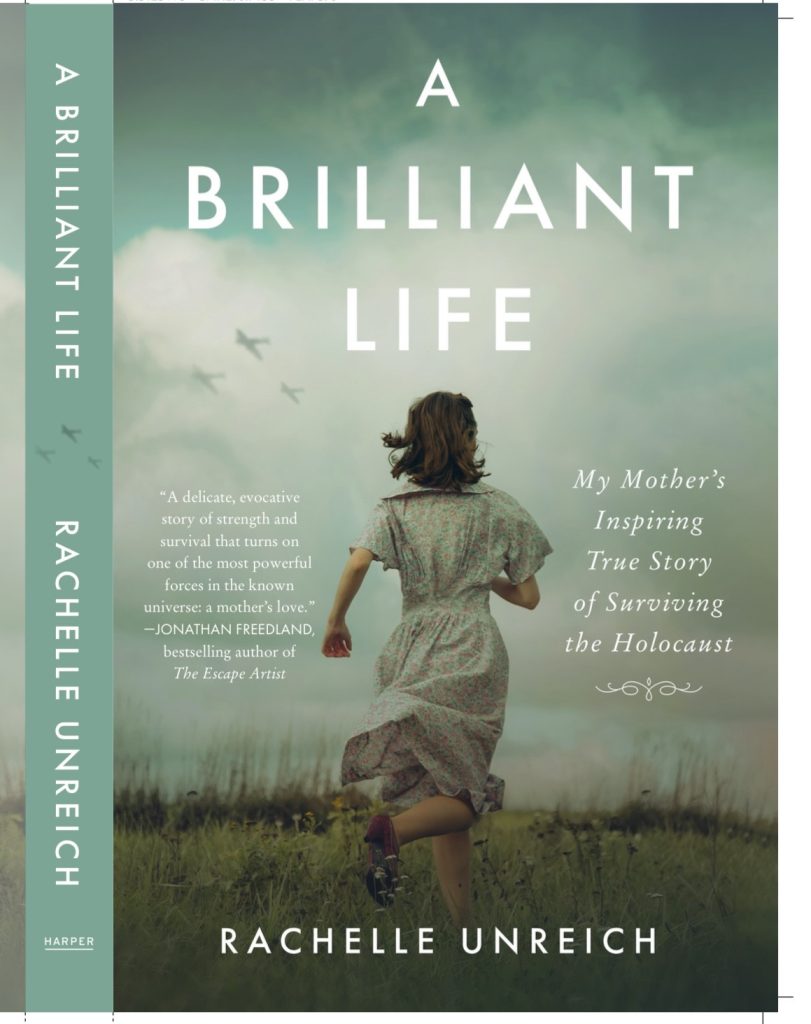

Within several weeks, I had found an agent. Within six weeks, I had a first draft. A year later, my book sold with an eight-imprint auction in Australia. Soon afterwards, Harper Collins in the US bought it in a pre-empt. It would go on to sell to the UK, to South Africa, to The Netherlands. And, soon after A Brilliant Life: My Mother’s Inspiring Story of Surviving the Holocaust was published, I received letters from readers, from all over the world, telling me how much Mira’s story had helped and healed them.

When my book was still in the pre-auction phase, I met with various publishers who wanted to buy it. One of them posed a question to me. ‘You’re in your mid-50s,’ he said. ‘You’ve been writing your whole life. How come you’ve never written a book?’

‘I didn’t think I could,’ I replied.

‘Who told you that?’

I thought for a moment, but I knew the answer. ‘I told me that.’

Rachelle Unreich has worked as a journalist for 40 years. Her first book, A Brilliant Life: My Mother’s Inspiring Story of Surviving the Holocaust, was shortlisted for four literary awards and has been published in Australia/NZ, USA/Canada, UK, South Africa and The Netherlands. Her essays appeared in anthologies On Being Jewish Now (edited by Zibby Owens) and Ruptured (edited by Lee Kofman and Tamar Paluch).

I absolutely adore reading ‘the story behind the story’ and yours, Rachelle, is so utterly inspiring! It has made me reflect deeply on my own writing (a work of creative nonfiction for a PhD, something that makes me question my own capability and purpose as a writer every day!) and what matters most: finding your intent, your legacy. Thank you for sharing! All my best wishes, Bianca

So glad to hear you’re inspired, Bianca! What is your CNF book about?

Thanks Lee! My work-in-progress ‘Caput Nebula’ is a braided memoir that weaves Narrative Medicine, women in literature, and the history of neuroscience around my 13-year journey to diagnosis of functional neurological disorder, very much inspired by, and in the vein of, Katerina Bryant’s hybrid memoir ‘Hysteria’ and Nicola Redhouse’s ‘Unlike the Heart: A Memoir of Mind and Brain’. It all began as an essay I wrote for Science Write Now (https://www.sciencewritenow.com/read/disability-and-body/caput-nebula) and has grown into a book-length project (and PhD) from there! So much of the writing, and writers, published on The Writer Laid Bare resonate, inspire and energise my words. Hopefully one day I can add my own small contribution to this vital space x

Dearest Bianca, I love what you’re doing. Read both memoirs you mentioned and loved them, and I’ll read your essay once I have a little free time. Thank you for your lovely words, as always x

Congratulations Rachel for writing this fine book. A legacy to be proud of.

I highly recommend this book!

Rachelle’s piece on not being able to write is beautifully written