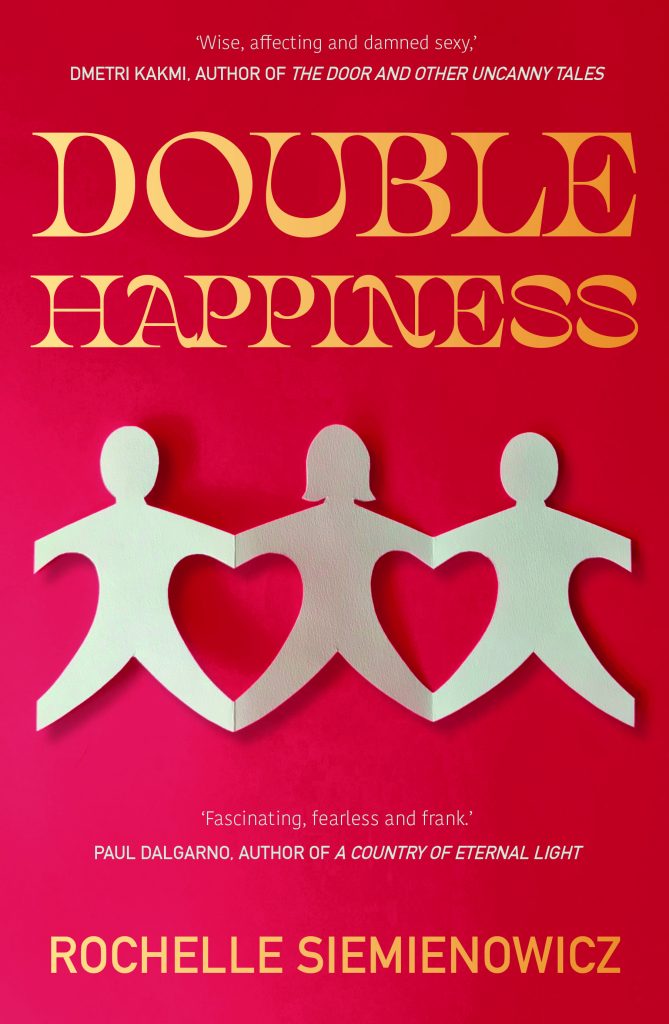

‘You might get some bloke at a writers’ festival who stands up in the audience and asks: “In your “research” (titter, titter) for this book, did you really have two dicks in your mouth?” – but that’s out of everyone’s hands, and you’ll close it down with aplomb.’ This is how my literary agent, Martin Shaw, reassured me when we were trying to find a publisher for my novel Double Happiness, a polyamorous love story informed by my own experiences with non-monogamy.

Double Happiness is necessarily a story with many graphic sex scenes. There are couples, throuples, foursomes and moresomes. And if I were the reader of such a book, I’d definitely also wonder how much of it was ‘true’.

But my story is crafted as fiction and told from three perspectives. This was the only way I could find through a maze of narrative possibilities and failed experiments with voice – including trying a traditional first-person memoir at one stage. It wasn’t prudery or shame that made me turn to fiction either, it was the fact that my memoiristic voice was insufferably self-mythologising and necessarily limited. I couldn’t ‘hear’ the multifaceted, multi-voiced truth of what I knew about ‘poly’. A memoir wouldn’t give the freedom to say what I wanted to say about love and its many shapeshifting, contradictory forms in long term relationships.

There are three narrators in Double Happiness: Anna, a restless wife and mother; Brendan, her anxious, loyal husband; and Jeremy, the dreamy, seemingly chilled-out lover who shifts the balance. Over seven years we follow these three characters as they struggle in different ways with desire, honesty, jealousy and forgiveness.

There’s no first person ‘I’ narrator here, but let’s be honest, the woman’s perspective is the dominant of the three. It’s very much her story and I have to say, despite my wishes for equality among the three, to me, she is the most compelling.

Like me, Anna is a Melbourne writer and journalist with rebellious, experimental urges and the desire to transcend traditional, suburban wifedom and motherhood. Unlike me she has black hair, a double-story house (mine has no stairs) and she’s not quite as self-aware. I like to think she’s a bit more beautiful and a bit less intelligent than I am.

But like me, Anna has written an explicit memoir, and as the years pass, her artistic quest to write a second book inspired by her life becomes more urgent and even desperate. How can she convey the complexities of her unconventional family? Where should she end the story? And how on earth will she find the time to write when she’s adopted too many creatures to love and look after?

This part of the novel is a kind of ‘metafiction’– fiction about the process of writing the thing itself – and metafiction is a central component of many of the works we now label ‘autofiction’. Writing for New York Magazine’s Vulture website, literary critic Christian Lorentzen argued that ‘…in autofiction there tends to be an emphasis on the narrator’s or protagonist’s or authorial alter ego’s status as a writer or artist… the book’s creation is inscribed in the book itself.’

Whoops, that sounds a bit like Double Happiness.

But when French critic and author Serge Doubrovsky first coined the term ‘autofiction’ in 1977, an essential component was having the author, narrator and protagonist share the same name, while not necessarily the same identity.

Phew. Clearly Anna is not Rochelle. She’s not the (sole) narrator either and we don’t hear from her in the first person.

But autofiction is an unstable and ever-evolving category – an increasingly popular one too, if your name’s big enough, which sadly mine isn’t. While bookshops don’t know where to put such books on the shelves, insisting on the distinction between memoir or fiction, the works of Rachel Cusk, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Sheila Heti and Ocean Vuong (to name just a few) demand a new category. And I believe that it’s in this genre that some of the most exciting new writing is happening.

So why was I reluctant when one of my endorsers, the writer and critic Jo Case, called Double Happiness ‘autofiction’ in her generous blurb for my media release?

‘Do I really want to use that word, that label?’ I pushed back. ‘I really don’t want people to talk about it like it’s a memoir, like last time.’

Last time, in 2015, I published Fallen. I wrote it as a novel narrated in the first person, but my publisher marketed it as a memoir. I agreed to this, even though the impulse to write that book came from my conviction that it was a work of invention rather than memory.

I recently read an interview with Miranda July in the New Yorker, about her sensational midlife novel All Fours, which is narrated by a ‘semi-famous artist’ very much like July. In her proposal for the book to the publisher, she reportedly said ‘This won’t ever be autofiction because, for me, nothing takes flight without the alchemy of invention.’

This rang so true for me.

‘Your novel so clearly is autofiction!’ Jo insisted. ‘It’s so meta in having your memoir within it. And your author bio and a quick Google search will tell people it’s autofiction.’

‘It doesn’t mean it’s a memoir,’ she reassured me. ‘You can be playful with autofiction, as you are.’

Then she mentioned Miranda July in her blurb, and Helen Garner, and I relaxed, because who wouldn’t want to be compared to them?

But here I am again, facing the book’s release and feeling uncomfortable and exposed. Why? Because, like it or not, I am going to have to talk about my life and myself, as much as about the creative work and the writing process.

As the psychologist Donald Winnicott said, ‘Artists are people driven by the tension between the desire to communicate and the desire to hide.’ Now I’m in the hiding phase. Here I am again, wishing I’d written something ‘simple’ and ‘pure’, a detective novel, say, set in a time and place far, far away.

But as any author knows, no matter how much your characters are ‘invented’, they’re always drawn from your own understanding of the world. Every writer’s exposed by their work – though of course memoir and autofiction come with the most obvious risks.

Finding courage and making peace with this exposure is a work in progress for me, as is accepting the fact that readers will think what they want of Anna – terrible, naughty, careless Anna – who may be a lot like me.

As the wonderful host of this blog, Lee Kofman, has said, we should write about what feels most ‘hot’ and urgent, and use the voice and form that’s right for the material. I wish I knew better what I was doing before I started, as some organised and prolific writers apparently do. Instead, every time I write I grope in the dark, not quite sure what I’m doing until it’s done, and then trying to justify and explain it.

Perhaps it all stems from childhood, when I learnt to read and began to obsessively narrate my life in my head, as if I were a character in a story. The flavour and genre of narration would depend on the book I’d been reading at the time. Nancy Drew turned my walks to school into mysteries with suspects, while Little House on the Prairie made every chore a calico-coloured pioneer adventure – even if I was scrubbing the bathroom with Jiff or watering Mum’s seedlings.

Now that I’m a woman in my 50s, and my darling Mum is avoiding conversations about my ‘unnecessary polyamorous novel’, I hear her voice from a few years ago when I told her what I was writing.

‘Must you keep turning your life into a story?’ she asked with a sigh.

Apparently, yes.

Rochelle Siemienowicz is a writer, editor and arts journalist. She is the author of Fallen: a memoir about sex, religion and marrying too young (Affirm Press, 2015) and the novel, Double Happiness (MidnightSun, 2024). Rochelle’s work has been published widely, including in The Age, SBS, Kill Your Darlings, The Big Issue, Metro, ArtsHub, Kalliope X and the anthology Rebellious Daughters. She has a PhD in Australian cinema and was for many years a film and TV critic and columnist. She lives in Melbourne with her two partners, her son, and a beloved but incontinent rescue dog. Website: https://rochellesiemienowicz.com/

Such a fantastic and well-crafted article, Rochelle! It was a pleasure to meet you at your Books@Stones launch last week, and wishing you every success with Double Happiness. I really enjoyed this piece, and am an avid reader of The Writer Laid Bare (huge credit to you, Lee!)

Many thanks for your kind words, dear Bianca, on my and Rochelle’s behalf! So glad you got to meet her.

Thank you Bianca, how lovely to bump into you again here! You did such a great job hosting at Books@Stones too. Really appreciate you reading this piece on Lee’s blog, which I must confess, caused me a little sweat and tears to produce. It’s so nice to hear that it connected. Thank you! I’m looking forward to reading more from you too.

A great article about the complexity of auto fiction, memoir and meta fiction. Hope your novel soars. I look forward to reading it.

Thanks Shannon! Really lovely to hear from a prospective reader too. Hope you enjoy.

Thanks Rochelle (and Lee) for this article. It’s a great discussion around the complexity of how a writer is so closely entwined in their characters and stories.

Meg, glad this piece spoke to you and I love how you articulated its essence. Thank you!