Why do I do this? What motivates my writing and makes it a necessity? Why do I not only expose myself, my inner-workings, but dream of my work to be read and appreciated?

I ask myself these questions when I open my eyes at exactly 5.42am in the morning, which is when my body clock usually kicks in. I get up and tiptoe to the living room with a pen and a notebook before my teenage daughter wakes up and demands my presence.

I’ve always had the creative impulse, the desire to create something out of nothing, in me. As a child, I spent hours sketching and painting, sculpting match-sized ballerinas for a shoebox theatre, sewing a fashion collection for my first Barbie borrowed for a weekend from a friend whose parents had just returned to Moscow from East Germany. I had never seen this kind of a doll before; it had a waist, hips and breasts. I made a fur coat, pantsuit and a ballgown for her.

Unsurprisingly, as an adult I forged a career as a theatre designer and worked all across the Soviet Russia, including Siberia, creating sets and costumes. I became a scenographer and interpreted other people’s stories via visual means. Yet, I began writing only after my emigration to Australia in the early 1990s. Perhaps what drove me to turn to writing was the need to express myself, to explain my new universe to myself and to tell the story of someone from other lands to others. I used writing as a way of thinking and exploring.

But were my stories unique or compelling enough to share them with the rest of humanity, beyond family and friends? I was a migrant, a so-called Russian Jew – Jewish ethnically but not religious (religion was outlawed in the USSR). That is what I have an ongoing urge to explore – where do I belong? Certainly not in the Soviet Union of the 1970s and 1980s, where I was a part of a hated minority.

I managed to leave Russia after fourteen years of trying. But did I belong with the Jewish community in Australia? I had never sat at a Passover dinner table until I arrived in Sydney as an adult with two children. I was seen as Jewish in Russia, but Australians, Jews included, saw me as being ‘Russian’. And could I become a part of the Australian theatre milieu? I sort of could and couldn’t. I didn’t find permanent employment with a theatre, but I ended up teaching set and costume design to undergraduates here; not a bad outcome in a country where sport is more popular than the arts…

I felt lonely in Australia without my theatre tribe or even a group of like-minded people. So, while my urge to create was partially satisfied at my teaching work, the desire to share my ‘otherness’ demanded a new outlet. As a theatre designer, I knew how to tell a visual story. Now, I had to learn a new craft, and to do so in my second language. (I had studied at a specialised English language school as a primary and secondary student in Moscow, where subjects were taught in English. We also had English and American Literature classes). Writing in Russian was easier for me, but by the time I translated what I wrote into English, the magic was lost, the sentences became awkward, the rhythm didn’t come through.

I read Shakespeare in Russian as translated by Boris Pasternak – a marvel. Perhaps one has to be born a genius poet to even attempt it. But most translated works I read, like Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita in English, have left me cold. So, I made the practical decision to write in English.

I wanted to write about people who, not dissimilarly to me, changed their destiny, abandoned or escaped their country of birth, shelved their mother tongue and not only survived, but flourished. As well as that, to tell the rest of the world of how we lived behind the Iron Curtain became my mission.

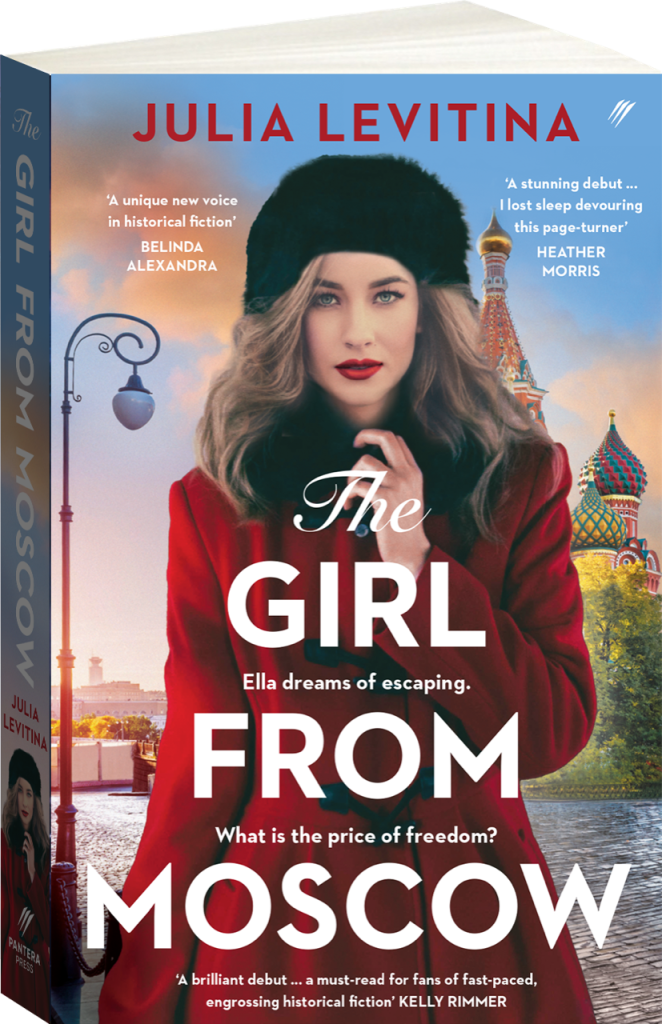

I single-mindedly persevered with writing my first novel, The Girl From Moscow, waking up every morning to write the story set in the 1980s USSR. The book, which told stories of dissidents as well as of those who tried (unsuccessfully) to live their lives ignoring the country’s terrible politics, was published last year. It took fifteen years of early mornings to bring it to completion, though I did take a five-year break to finish my Masters of Design and… Get a divorce.

The 5.42am waking-up habit has stayed with me after my first bookwas completed. These days I write in the hope that my new novel-in-progress, set in Stalin’s Russia and the Australian outback, will add a new layer of understanding of the migrant experience. I write and write, even though no one is waiting for my next book.

For me, it actually feels liberating to write without any formal deadlines. I have one book published and I know I will finish the next one. The first draft of Beyond The Pale – the working title of my current novel – has been short-listed for First Chapters Historical Fiction Competition in the United Kingdom and highly commended at The Wingate Award for Unpublished Manuscripts. This is encouraging, but would I stop writing if it hadn’t happened? The answer is ‘no’. Whether my second novel will get published or not, I will continue to get up at the crack of dawn to write. Why? It is simple. I get high after ‘have written’. Writing gives my life a structure and a purpose. And this is why I write.

Julia Levitina grew up in Moscow with her Ukrainian Jewish mother and grandmother, both Holocaust survivors. She worked as a theatre designer before immigrating to Australia in 1991 with two children and $200. Julia completed Masters of Design at University of Technology Sydney. While teaching set and costume design, she wrote The Girl from Moscow – shortlisted for the ASA/HQ Commercial Fiction Prize and published in 2024 by Pantera Press. Julia’s second novel-in-progress was shortlisted for Historical Novel Society UK First Chapters Competition and highly commended at Wingate Award for Unpublished Manuscripts. She lives in Sydney’s east. More information at Julialevitinaauthor.com

What an inspiring glimpse into Julia Levitina’s world and her writing practice.

So glad you liked Julia’s post, Kyra! It inspired me too.

Sounds fascinating. Good on you for never ever giving up. I will the Moscow book with great interest.

I think you’ll really enjoy it, dear Karen.