When I set about writing my memoir Split, telling the story of my life with Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD) – or as it’s called today, Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), I envisaged that it would be a mix of poetry and prose. I wanted to write episodically, to mirror what was going on in my kaleidoscope brain. Like other people with my condition, I have in my mind individual voices and personalities, called alters by professionals, that constitute the mental system that lived our abusive childhood. I refer to my alters as The Girls. As an adult, The Girls have stayed with me, mostly quiet, but occasionally triggered by distressing situations. I hoped that the mosaic fragments that I wrote about both our childhood and the adult consequences of those years, would tell my story of living with MPD.

What I failed to appreciate was that no matter how much writing my story this way made sense to me, it was incomprehensible for readers with a neurotypical brain. So, I embarked on my next draft (and next, and next …) in an effort to find a more coherent way to communicate what it was like for me to live out the cacophony in my head.

This required a huge rethink on my part, stepping back to understand the big picture of the story I was trying to tell. Firstly, I wanted to paint a realistic picture of what living with MPD was really like for me, not the Hollywood hype, where aggressive psychotic alters were portrayed as murderers, wreaking havoc on society. Far more realistic, and much less dramatic, were the day-to-day ins and outs of my existence living with The Girls in my head. Second, I wanted to enable alters to tell their own stories. It was important to acknowledge that, after all was said and done, mine was a shared history, and the abuse from both my parents and a pedophile ring we were trapped in, was what the alters had lived through to protect me.

During the writing process, it would be important for me and The Girls to confront some of the stories and pain that they experienced. I naturally avoided these memories, as per my tendency towards dissociation. It’s part of the art of being multiple, that I have been able to segment off my experiences so that they were hidden from me. That’s why I needed the alters to be a part of my storytelling. If they used their own words, their account of trauma would be much more accurate. More so, telling their story in third person was too safe, too easy, and would not draw the reader in and elicit an understanding of the depth of trauma that had to occur for my system of alters to be created.

So, I took all the episodic bits that had formed my first draft, some written by alters and some by me, and put them each on index cards. Laying these out on a large table gave me the ability to rearrange and find a way to put all these disparate stories from The Girls into a chronological structure of what happened to us. This formed the scaffolding around which a tangible story could unfold. As I moved these index cards around, removing some and replacing them with others, a linear three-part structure of my life emerged. The early years were captured in Annie’s Story (she is my primary alter whose responsibility was to give The Girls their ‘jobs’), my adult years became Maggie’s Story (where I returned to consciousness at the age of 33 and began living my life), and concluding with Co-Existence, all about Annie and myself (and The Girls), learning to live together. This structure was the easy part, and came together quickly.

The real challenge was to invite the reader inside my multiple world and experience, first-hand, the lives that my alters lived. To let The Girls express their own stories was daunting. I was (and continue to be) grateful for the existence of my alter named Writer. Writer experienced no trauma. Instead, they existed as a grey fog to nurture our writing. Often with Writer it is a slow process where I look internally to see them formulating thoughts and ideas while I go about my day, grocery shopping or making dinner. Eventually, they’d provide clarity, making practical, often insistent suggestions regarding how to capture The Girls’ thoughts in writing. It was Writer’s idea to distill down the experiences of The Girls into one chapter, painting a clear, if not somewhat simplified, picture of the trauma they endured.

To do this I had to create an environment where The Girls could safely share their stories. I picked up my computer and headed outside. I hoped plants and birds would inspire Writer (and The Girls) more than the four walls of my study. It was there that the chapter Working Girl was birthed. I sat at the computer and made the conscious decision to step aside; vacate, so they could write. A process that to others might seem strange and bizarre, but was second nature to me. I looked inside, stepped to the back of my brain and literally handed over my body to Writer as they channeled the words of The Girls.

I knew that each of them wanted anonymity in their writing (except for Writer, they were content with being known). Each alter was given a name that described their responsibilities and place in the system, e.g., Little Girl, Pretty Girl, or Runaway Girl, to show that my alters had distinct personalities and perspectives. From there it was a simple process. Each of the seven alters who decided to participate told their story and Writer transcribed it, word-for-word – the abuse and how they survived. During this process I mentally retreated. My fingers typed, a conduit for The Girls’ voices as they told their story.

It was a first draft, of course – but the voices of The Girls spoke – communicating who they were and WHY they were, what purpose they served in protecting me. This was at the heart of my story, giving them veracity in their own right as individuals who lived my life (albeit in segmented fragments).

While writing from this shadowy place has been vulnerable, it has also assisted my healing process. Later in the book I describe how the writing process coalesced. I was able to choose those pieces that represented the thread at the heart of my story and in this way exercised ownership and control over the abuse that we lived through. The sharing of my story with my writing group was also therapeutic as they began to understand my story and embraced the totality of who I was.

I suspect anyone who writes memoir, or something else exposing and intimate, experiences something akin to what I went through, digging deep to find the important parts of what we are writing – a process that is both healing and transformative. Each time we return to our manuscript to hone our words, polish our phrasing, cut unnecessary verbiage, it rings true and clear, becoming a story that is accessible to the reader.

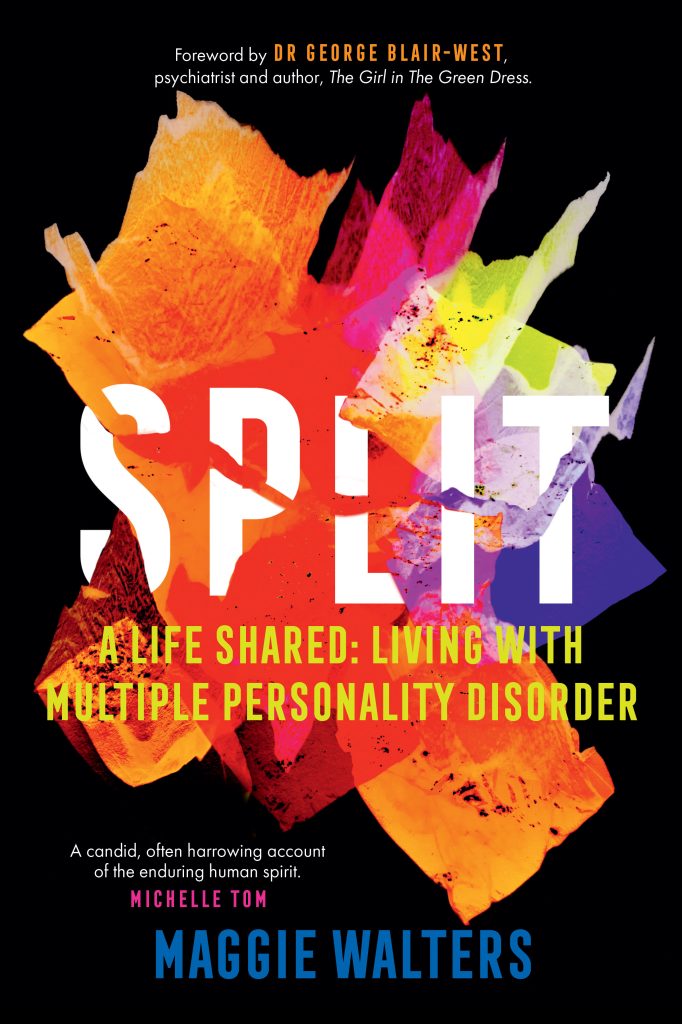

SPLIT is Maggie’s debut work and an early version was long-listed for the 2022 Richell Emerging Writers Prize. In her work she shares her courageous journey towards wholeness and challenging stereotypes around MPD/DID. She is committed to encouraging others to break down the barriers and stigmas around mental health. Maggie lives in the Northern Rivers, where she develops her craft and raises her family. For more information about how Maggie is working to change the narrative around mental health, visit www.maggie-walters.com.

Maggie, thank you for your endurance, inspiration, and for your bravery in sharing your story.

I will be reading this memoir. It sounds compelling and unique, with huge depth. What a labour to write a story – and one that is little known.

Great to hear, Seana! It is a wonderful memoir indeed.

I like how The Writer goes about their daily business, all the while formulating thoughts and ideas. So true.